Continuing his exploration of the rich and fascinating papers of West Lothian laird Sir Walter Dundas (1562-1636), Dr Alan MacDonald grapples with an age-old problem: how many legs are there on a goose?

Follow Alan on Twitter at @estaitis

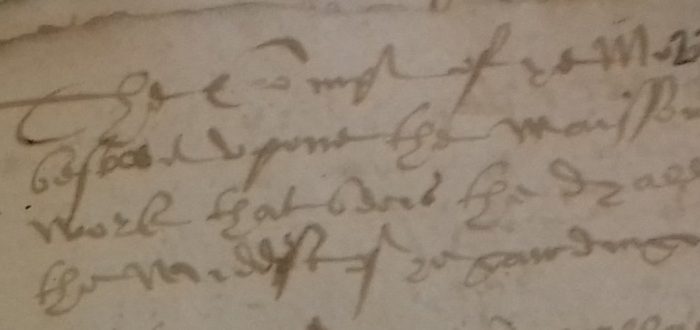

In 1616, John Meek was in arrears of rent to the laird of Dundas in West Lothian. As well as owing £3 6s 8d (just over 2 weeks’ pay for an unskilled labourer) and 6 firlots of oats (about 1½ wheelie bins), he owed ‘1 guse, 3 legs of a guse’. The past is a foreign country – they do things differently there. In this post we’ll be using the records of the Dundas estate to explore an aspect of this truth. We’ll return to the geese later.

Buying and selling through the ages

A great deal of trade in early modern Scotland was done at Mercat Crosses. This example is from Prestonpans.

How we pay for things has changed a lot over the last 50 years. With contactless payments and internet banking it’s hard for most people to remember when paying had to be by cash or cheque, and you could only get cash when the bank was open. It’s even harder to imagine a world where transactions didn’t need money or could involve other things alongside it. Yet for many in the early modern period, that was quite normal and they managed just fine.

It’s often assumed that in ‘the olden days’ people used barter: let’s say I had some beans and you had some wool that I wanted. To barter, we would have to agree on the relative value of the two commodities so a certain weight of beans could be exchanged for a certain weight of wool. The problem is, there’s no evidence of a system like that actually operating and there are good reasons why: it makes every transaction uncertain (you have to spend a lot of time negotiating), and the person who has the wool might not want beans. There were three ways round this. One was that most basic commodities had agreed cash values, set annually by local courts: you didn’t need to haggle because people knew what things were worth. Another was that there was actually enough cash around to avoid those awkward situations when I had beans and wanted wool and you had wool but didn’t want beans. I could buy your wool because I could sell my beans to someone else for money.

The third solution involved a very different concept and will get us (thanks for your patience), to the three-legged goose.

Paying rent in early seventeenth-century West Lothian

Before the industrial revolution, most people lived in the countryside. They survived largely on the crops they grew and the animals they raised. While they didn’t have much call for cash, they all had a landlord and they owed him (or her) rent. This is where it gets interesting, as revealed in the opening anecdote. Surviving rentals from the Dundas estates reveal a lot about the variety of things that you might pay your rent with.

Most people paid most of their rent in cereals (oats, barley, wheat), usually a fixed amount based on how much land you had and how good it was. The better the land, the more wheat was grown, the poorer the land, the more oats. In a good harvest, you would have some surplus to sell, although in a bad year you might struggle to make it through to the next harvest. The fact that rent could be paid ‘in kind’ rather than money shows that early modern people had a more complex understanding of what an economic transaction was than we do. Part of your rent could be due in money but the other bits weren’t substitutes for money, they were a different way of paying.

In some parts of Scotland, rent might be due in butter or cheese and, on the Dundas estate, most people paid some rent in poultry. In 1603, the laird received more than 385 capons (young cockerels), which were alive (no fridges or freezers). Incidentally, this also tells us that chicken was part of most people’s diet (not all the surplus cockerels went in rent), and eggs must have been too. Now why did I say ‘more than 385 capons’? Well, one tenant, Richard Laurie, paid half a capon. He probably didn’t require a really sharp knife, though. He will have paid one capon every two years. (We’ll get to those geese eventually, never fear!) Richard Laurie was due half a capon because the rate was one capon per acre and he had half an acre.

A Still Life with Dead Partridge, Pheasant, and Hunting Gear by Hendrick de Fromantiou, 1670.

Can a goose have three (or more) legs?

So at last we come to the ‘one guse, 3 legs of a guse’ that John Meek owed. Geese were common domestic fowl. They were cheap to keep because they eat grass; they provided rich meat and their wing feathers were also used for quill pens. Like the capons, they were paid as live birds. So, since these legs were not portions of meat, you might imagine ‘three legs’ was one and a half geese (given the number of legs on your average goose). But if that was so, John’s arrears would surely have been recorded as 2½ geese, not one and three halves. It’s very hard to tell though, because Scottish Language Dictionaries don’t have any record of this meaning of ‘leg’, nor does the Oxford English Dictionary. So it turns out I discovered a new meaning of the word! My best guess is that it comes from a way of dividing rent due in livestock. A piece of land might be due one cow: if that land got divided between four tenants, each one would pay a ‘leg’ (quarter) of a cow. ‘Legs’ thus came to mean ‘quarters’, so John’s rent included the obligation to pay a goose and three quarters. He probably paid two geese in three out of every four years and one in the fourth year, or he may have converted the value of geese into money. Either that or I’ve stumbled across the existence of four-legged geese in early seventeenth-century Scotland!

Web link

Scots Dictionary Online: http://www.scotsdictionaries.org.uk/

Comments are closed.