The Union of 1707 did not come out of nowhere; Scots had been discussing the concept almost ceaselessly throughout the 17th century. Dr Allan Kennedy outlines the major models of Union they came up with, demonstrating that the form adopted in 1707 was by no means the only possible version.

Follow Allan of Twitter at @Allan_D_Kennedy

James VI & I, after John de Critz.

As he reflected after 1603 on his new status as king of both England and Scotland, James VI & I was profoundly dissatisfied. Despite sharing a sovereign, his two kingdoms (Ireland, which he also ruled, was always kept in a different mental category) remained completely distinct, both in nature and in law, and this struck James as unsatisfactory. It would be much better all round – much neater, much more stable, and much more ‘glorious’ – if James could achieve what he called ‘a more perfect union’. In so pondering, King James established himself as perhaps the highest-profile individual to engage seriously with the question that would, perhaps more than anything else, shape Scotland’s 17th century: Union.

Scots had in fact been thinking about Anglo-Scottish Union long before James VI inherited the English throne. Most famously, the great 16th-century scholar John Mair had been a vocal advocate for Anglo-Scottish amalgamation, arguing that Union would put an end to the Scots’ destructive habit of going to war with the English (and vice-versa, of course). But in the context of shared monarchy after 1603, Union took on a new relevance. There was anxiety from the start about what the king’s newfound residence in London would mean for Scottish governance, but also for Scottish autonomy. These concerns were summed up in retrospect by George Mackenzie, Lord Tarbart, a supporter of the 1707 Union who explained in his book, Parainesis Pacifica (1702), that the structure of shared monarchy had proved unsatisfactory:

We are accustomed, as if we were obliged, to bestow our Blood and Goods, in War, against whoever are in War with England: To expose ourselves, to the Enmitie of their Enemies, Though our Ancient Allies, Confederates and Friends; And all this to Enhance more of Trade, and thereby of Treasure to England; And so soon as the design is attained, then no Nation so much, at least none more, excluded from all benefit of English Trade and Plantation, then Scots-men are; The injustice whereof, is become a National Complaint.

The idea that conglomerate monarchy potentially left Scotland with the worst of both worlds, following their king to go along with whatever benefitted England while foregoing the resulting rewards, ensured that the problem of how to recast Anglo-Scottish interaction was never far from Scots’ minds during the 17th century. As they grappled with the issue – sometimes enthusiastically, sometimes reluctantly – four distinct ‘models’ of Union gradually crystallised. Each of these, coming to the fore at separate points in the century, imagined a different future for Anglo-Scottish relations, and right up until 1707 it was not clear which, if any, offered the most plausible route-map for uniting the kingdoms (assuming, of course, Union was desirable at all – but that’s a subject for a different blog post!).

Models of Union

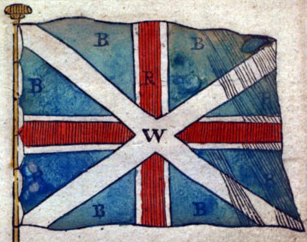

The first model for Union was that preferred by James VI himself. His fervent hope was that he could forge England and Scotland (Ireland he left out) into a new and greater British kingdom, erasing the Anglo-Scottish border in the process. At one point, he explained his vision using the analogy of ‘little brookes’ flowing into larger rivers and losing their distinctiveness as they mixed. Even if he recognised that, in practice, the process was unlikely to be quite so comprehensive, James was still aiming, in essence, at an ‘incorporating’ Union – that is, the merging of Scotland and England into a brand new political entity, with both ancestral kingdoms ceasing to exist. This was (on paper at least) the route that would ultimately be taken in 1707, but it was not one to which either James’ English or Scottish subject were amenable in the early 1600s. Faced with implacable resistance on both sides, the king had given up by around 1607, contenting himself with cosmetic changes like a new flag and the symbolic, self-awarded title, ‘King of Great Britain’.

The Solemn League and Covenant (1643)

The second model of Union was very different indeed. It was an idea sometimes known as ‘confederation’, and it was articulated and pursued most energetically by the Covenanters, Presbyterian opponents of Charles I who controlled Scotland during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (1639-51). A ‘confederal’ Union did not necessarily imply the creation of new structures or a new polity, although these things might develop. Rather, the point was for Scotland and England to co-operate closely, co-ordinating their activities for shared purposes. The key text of ‘confederal’ thinking was the Solemn League and Covenant (1643), a treaty between the Covenanters and the English Parliament that pledged co-operation in defeating Charles I and establishing religious orthodoxy across the British Isles. This joint effort was co-ordinated by a Committee of Both Kingdoms, containing representatives of both the English and Scottish Parliaments.

A ‘confederal’ model of Union, therefore, implied that Scotland and England would continue to exist, but would work together as equals in a shared British space. The attraction of this idea to Scotland, in the sense that it negated England’s otherwise overwhelming advantages in size, power, and wealth, was obvious, but confederation was less intrinsically appealing from an English perspective. This, perhaps, explains why the ‘high point’ of confederalism was the early- to mid-1640s, when England was badly weakened by Civil War. Once something resembling the ordinary balance of power was restored, confederal Union rapidly lost it lustre.

If the Covenanting vision of Union sought to maximise Scottish influence within any Anglo-Scottish conglomerate, the precise opposite result flowed from the next model of Union – the Commonwealth. Following the conquest of Scotland by the New Model Army in 1651, a ‘Tender of Union’ was imposed that removed all the main structures of Scottish national governance, to be replaced by direct rule from Westminster. Key features of English political culture, most notably religious toleration, were imposed by decree. Where elements of Scottish distinctiveness were allowed to persist, for example in law and the legal system, new English supervisory structures were created. Alongside all this, the Commonwealth maintained a very heavy (although gradually reducing) military presence in Scotland throughout the 1650s.

The Cromwellian model of Union, in short, was de facto annexation, predicated on Scotland becoming part of an enlarged English state and being subject to direct English supervision. It was a model that drew upon a long-established strain in English thought which hankered for a ‘Greater England’, and naturally enough it held limited appeal for most Scots. Its implementation in the 1650s therefore depended entirely upon England having the will and wherewithal to sustain it. Neither of these impulses survived the restoration of Charles II in 1660, and so the ‘Tender of Union’, like almost every other feature of the Commonwealth state, was swept quickly away.

Charles II, under whom negotiations for commercial Union took place. By John Michael Wright or studio.

Three distinct models of Union had thus emerged by the 1650s. But there was still time in the 17th century for a fourth alternative to develop. This was ‘commercial’ Union, a scheme that emerged in the late 1660s. The idea was to forge closer links between Scotland and England purely on commercial grounds – in effect, to develop something like a pan-British free trade zone, without much in the way of political Union to go with it. ‘Free trade’ held attractions on both sides, although especially so for Scots hungrily eyeing England’s internal and imperial markets. But it also came with well-articulated risks in the form of additional competition.

With the encouragement of Charles II, the concept of commercial Union was actively discussed by panels of Scottish and English negotiators in 1669-70, but ultimately nothing came of the talks. This was partly because neither side was entirely persuaded by the proposition, and partly because the discussions were, to some extent, the product of temporary political pressures in both Scotland and England; when these moments of crisis passed, so did governmental interest in commercial Union. Nonetheless, the negotiations of 1668-9 had produced a model of Union, focused on trade rather than sovereignty, that was quite distinct from its Jacobean, Covenanting and Cromwellian predecessors.

Conclusion

None of the ‘models’ of Union outlined above were entirely straightforward, and within the parameters of each a wide array of different forms were conceivable. The possible fate of Scots law is a good indicator of this. An ‘incorporating’ Union, such as the one imagined by James VI & I and ultimately affected in 1707, might easily have implied protecting the distinctiveness of Scottish law in perpetuity; fostering gradual alignment of Scots law onto English law; or the amalgamation of both systems into something wholly new. Similarly, the de facto annexation of Scotland carried through in the 1650s could have facilitated – as indeed it was sometimes assumed that is would – the complete eradication of Scots law, but in the event the Commonwealth opted to permit its continued operation, albeit under English supervision. These ‘models’, then, were not hard-and-fast templates for Anglo-Scottish integration, but were rather general approaches defining the broad, underlying character of any proposed new polity.

Ultimately, of course, no form of Union was affected in a durable way prior to 1707. In essence, that was because the ‘models’ of Union all foundered on two issues. Firstly, they required Scots to be confident that Union would not impact excessively on Scottish distinctiveness, or to be comfortable with its loss. Neither of these was forthcoming. Secondly, each model needed the active interest of the English, rooted in a feeling that Union, whatever form it took, was of some advantage to them. With the temporary exception of the 1650s, such engagement was always missing – put simply, there never seemed to be anything ‘in it’ for England. Hobbled by Scottish anxiety and English indifference, the Union projects of the 17th century all proved dead letters. It would take the exceptional constitutional and geopolitical circumstances of the early 18th century to cut this Gordian knot.

Further reading

J.R. Ford, ‘Four Models of Union’, Stair Society Miscellany 7 (Edinburgh, 2015), 179-216

A.I. Macinnes, Union and Empire: The Making of the United Kingdom in 1707 (Cambridge, 2007)

K.M Mackenzie, The Solemn League and Covenant of the Three Kingdoms and the Cromwellian Union, 1643-1663 (London, 2018)

R.A. Mason, ‘Debating Britain in Seventeenth-Century Scotland: Multiple Monarchy and Scottish Sovereignty’, Journal of Scottish Historical Studies, 35:1 (2015), 1-23

S. Waurechen, ‘Imagined Polities, Failed Dreams, and the Beginnings of an Unacknowledged Britain: English Responses to James VI and I’s Vision of a Perfect Union’, Journal of British Studies, 52:3 (2013), 575-96

C.A. Whatley, The Scots and the Union (Edinburgh, 2007), esp. chapter 2

Comments are closed.