In an exclusive preview of his new book, Professor Graeme Morton explores the rise of meteorological science in the nineteenth century, and asks how it might have related to the Scottish experience of mass emigration.

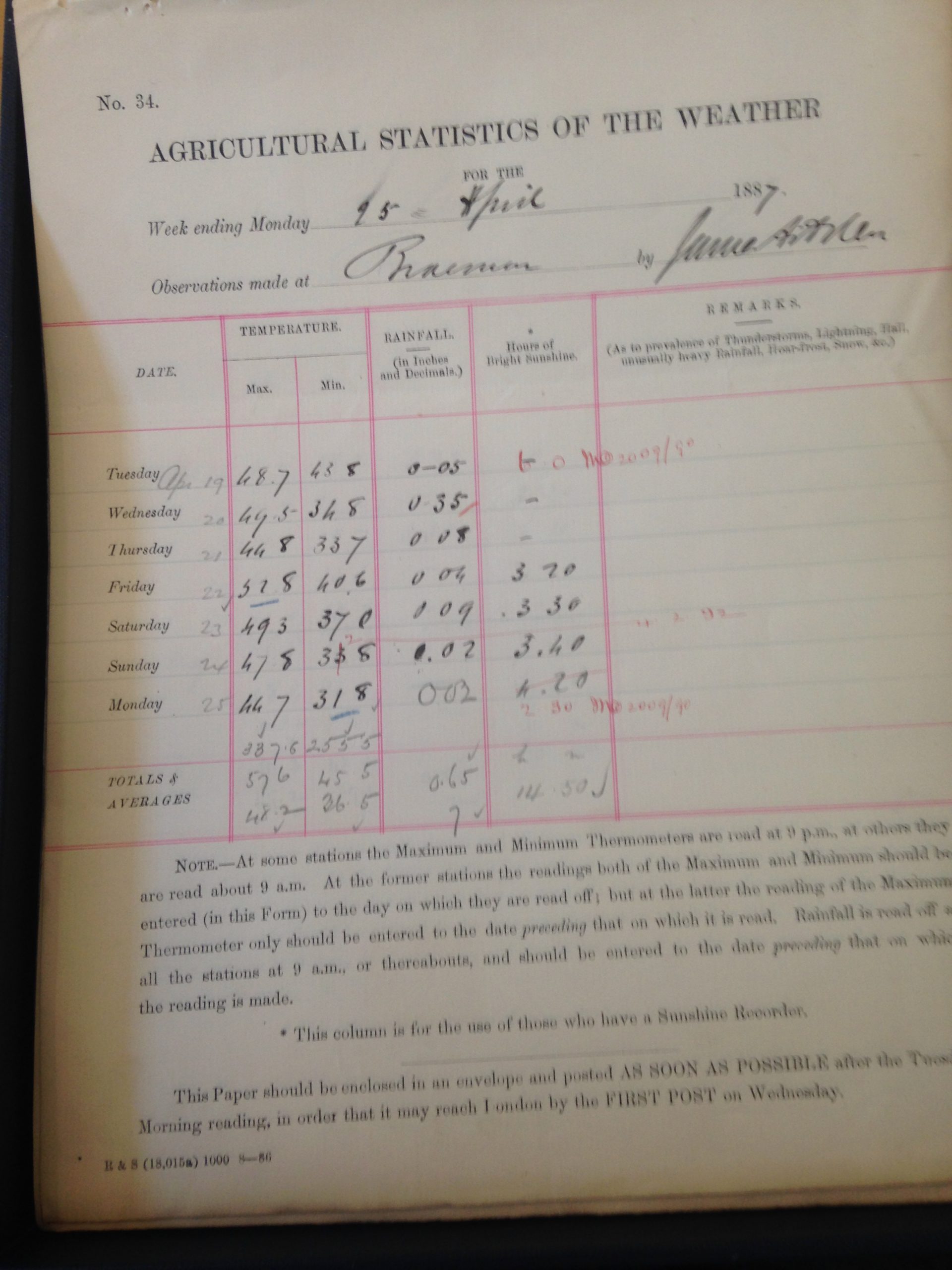

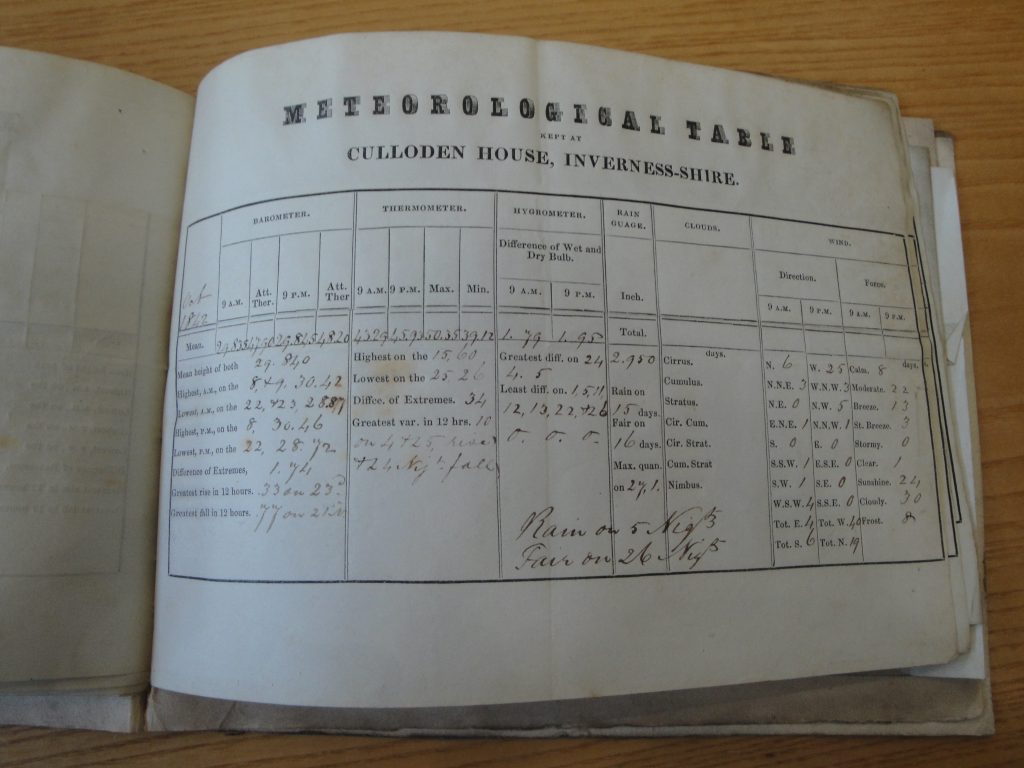

Even when the rain and temperature gauge, the barometer and anemometer were commonly used to record meteorological observations, the popularity of proverbs to foretell the day’s weather, or that of that season, remained strong. With the creation of a meteorological committee within the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1820, and the Scottish Meteorological Society instituted in 1855, the impetus to record daily meteorological observations grew steadily. But for some, regardless, the old farmer and the active mariner knew best. If fine weather was seen to come too early in the year, then unwelcome consequences could be expected:

If the grass grow in Janiveer

‘Twill be the worse for all the year

[Chambers’ Popular Rhymes of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1841), p. 363].

Nae hurray wi’ your corns,

Nae huuray wi’ your harrows;

Snaw lies ahint the dyke,

Mair may come and fill the furrows

[Rev. C. Swinson, A Handbook of Weather Folk Lore (Edinburgh, 1873), p. 12]

While particular cloud formations would suggest high winds and difficult sailing conditions:

Mackerel’s scales and mare’s tails

Make lofty ships carry low sales

[C. Clouston, An Explanation of the Popular Weather Prognostics of Scotland on Scientific Principles (Edinburgh, 1867), p. 13]

Yet the nineteenth century was when the scientist looked to build both credibility and use value from the relentless task of meteorological observation and for the risky business of forecasting. Not only were questions asked about weather patterns, but also about identifying and measuring meteorological causality. Skilled amateur scientists such as the Reverend Charles Clouston tested the credibility of proverbs. His peers searched for relationships between climate change and physical and mental health. They also conducted investigations into the willingness of Scots to move around their country and to move overseas in response to environmental challenge. Much of Scotland’s soil is thin and rocky, and a higher percentage of this landmass—compared to England and Ireland— lies 500 feet or more above sea level. It is a climate to escape from, or so argued the emigration agents who extolled a life overseas. Come to Prince Edward Island, it was said, ‘because mankind must increase very fast in such a climate’. One former resident of Bathgate wrote home about the benefits of New Zealand in an article first published in the Glasgow Chronicle:

Our climate is 10 deg. S. of that of Glasgow, and a few degrees warmer; however, at the warmest not intolerable, but very delightful even at noon … We have a very pure healthful air—an almost unclouded sun—a soil astonishingly grateful to the labours of industry. This country is thickly intersected with delightful rivers and lakes, stocked with fish, if we had time to catch them

When added to a common sense understanding that emigration rates rose after periods of rough weather had left crops damaged, rivers and drainage systems overwhelmed, raised food prices, and weakened health, the spread of instrument observations allowed for meteorological relationships to be tested. Scotland had long lost significant proportions of its population to emigration, with an estimated, 2.33 million people having departed between 1825 and 1938. Over the period 1795 to 1850, the mean temperature of Scotland was 8.2°C, and ranged from a low of 6.9°C in 1799 to a high of 9.8°C in 1846. The 1780s and 1790s were decades characterised by their cold winters and warm summers. The 1820s were generally wet and warm, although there were heavy snowfalls in 1836 through to 1840. The growing season came earliest in 1845 and 1846, and these were years when the price of oats was relatively expensive, and in 1846, with tragic consequences, the potato blight spread. The years through to 1850 were some of the stormiest; the 1860s was a warmer period, and the 1880s was a period of cooler summers, although drier and with milder winters. Scotland was a cold country but it would get warmer. Through the decades 1901–50 the average temperature was 0.2 °C above the mean for 1701–1950, a figure that increases to 0.9 °C when only the 1930s and 1940s are measured. Five of the ten hottest years have been since 2002, whereas five of the ten coldest years were experienced before 1900.

When added to a common sense understanding that emigration rates rose after periods of rough weather had left crops damaged, rivers and drainage systems overwhelmed, raised food prices, and weakened health, the spread of instrument observations allowed for meteorological relationships to be tested. Scotland had long lost significant proportions of its population to emigration, with an estimated, 2.33 million people having departed between 1825 and 1938. Over the period 1795 to 1850, the mean temperature of Scotland was 8.2°C, and ranged from a low of 6.9°C in 1799 to a high of 9.8°C in 1846. The 1780s and 1790s were decades characterised by their cold winters and warm summers. The 1820s were generally wet and warm, although there were heavy snowfalls in 1836 through to 1840. The growing season came earliest in 1845 and 1846, and these were years when the price of oats was relatively expensive, and in 1846, with tragic consequences, the potato blight spread. The years through to 1850 were some of the stormiest; the 1860s was a warmer period, and the 1880s was a period of cooler summers, although drier and with milder winters. Scotland was a cold country but it would get warmer. Through the decades 1901–50 the average temperature was 0.2 °C above the mean for 1701–1950, a figure that increases to 0.9 °C when only the 1930s and 1940s are measured. Five of the ten hottest years have been since 2002, whereas five of the ten coldest years were experienced before 1900.

Britain’s temperate climate, even given recent concerns over climate change, has not led to climate refugees as observed elsewhere. Yet climate variation has been the backdrop to Scotland’s emigration and diaspora history. Contemporary research into environmental determinism made the case for emigration by emphasising the health and prosperity found in climates overseas. Emigration agents addressed the public through the press, through meetings, and through evidence given to government committees to boost the appeal of the settler destinations. Economic and demographic factors underpin emigration, undoubtedly. But by building upon the work of historical climatologists and by deploying long-run meteorological data it becomes possible to better understand the choices Scots made when leaving the cold country.

Graeme Morton, Weather, Migration and the Scottish Diaspora: Leaving the Cold Country (London: Routledge, 2020): https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429329500

Comments are closed.