With Hallowe’en nearly upon us, Dr Allan Kennedy gets into the spooky spirit by telling the story of the supposed witches’ coven discovered in Crook of Devon, Kinross-shire, in 1662.

Follow Allan on Twitter at: @Allan_D_Kennedy

Between 1563 and 1736, roughly 4,000 Scots, mainly women, were accused of witchcraft. Of these, perhaps 2,500 were found guilty and executed. Most of Scotland’s witch-hunting was concentrated in a few intense periods of panic lasting a year or two, and the majority of it took place in the Lothians, Strathclyde, or Fife. But in 1662, at the height of the biggest witch-panic of them all (the so-called ‘great’ witch-hunt of 1661-2), the horrors of witch-persecution came to the tiny county of Kinross-shire, and in particular to Crook of Devon, a small settlement roughly equidistant between Perth, Stirling, and Dunfermline. Here, the discovery of an alleged witches’ coven led to a series of dramatic trials – with tragic consequences.

The River Devon, near Crook of Devon. Photography by Callum Black.

The Crook of Devon trials were staggered across four separate court sittings between 3 April and 8 October. Thirteen people were accused: Agnes Murie; Bessie Henderson; Isabel Rutherford; Robert Wilson; Bessie Neil; Margaret Lister; Janet Paton elder and younger; Agnes Brugh; Margaret Hoggin; Janet Brugh; Christian Garvie; and Agnes Pittendreich. Together, these individuals were suspected of forming their own little cell, and indeed when they came to trial, their confessions near-unanimously suggested exactly that. As a result, they were almost all convicted, and thus sentenced to death by the traditional method reserved for witches: they were to be taken ‘to the place called the Lamlaires bewest the Cruick Miln’ and there ‘stranglit to the death by the hand of the hangman, and thereafter their bodies to be burnt to ashes’.

Only two of the accused witches escaped the death penalty. The first, Margaret Hoggin, who was around 80 years old, died before her case could be decided. Meanwhile the second, Agnes Pittendreich, was found to be pregnant, and so proceedings against her were postponed until after the birth. She is never mentioned again, so perhaps her pregnancy allowed her to escape the garotte completely.

The Witches’ Deeds

In broad terms, the witches were accused of two main things. The first was casting evil spells. Margaret Lister, for example, was accused of visiting the ‘falling sickness’ – the seventeenth-century term for epilepsy – on several people around Crook of Devon who had angered her. Janet Paton elder supposedly cursed a horse belonging to one Andrew Huston after it destroyed some of her property, the beast promptly sickening and dying. Agnes Muire allegedly targeted a man named Henry Anderson, whom she struck dumb (apparently by offering him some enchanted snuff) after he had failed to fertilise her fields with lime. Dark magic of this kind was widely feared not only because it was dangerous, but also because it was disruptive. Seventeenth-century society depended on order, and on everybody knowing their place. By casting spells like these, witches disrupted that cosy picture, and were loathed accordingly.

The second big accusation levelled against the thirteen witches was that they had communed with Satan. The Devil was central to Scottish witch-belief, since it was assumed that witches acquired their power by signing up as his servants. The Crook of Devon confessions contain some intriguing details about this covenant with Satan. The Devil always appeared to the witches in the form of a man, and usually offered them power or riches for becoming his servant. Giving in to this temptation, the witches would renounce their baptism and pledge themselves instead to Satan, usually through the following ceremony, as described in the indictment against Margaret Hoggin:

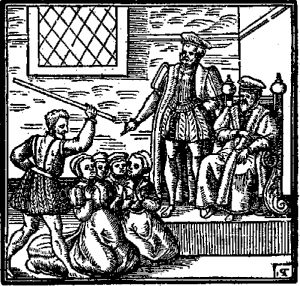

Witches being questioned, from Daemonologie (1597).

[You] put ane of your hands to the crown of your head and the other to the sole of your foot and delivered all [in between] to Sathan’s service.

This new allegiance was typically sealed by Satan bestowing the ‘witch’s mark’, a special blemish on the skin that could neither feel pain nor bleed. He would also sometimes give his disciples a new name: Agnes Murie, for instance, became ‘Rossina’. In the case of the women, the Devil would also copulate with them – an experience that was apparently unpleasant, since several confessions noted that his ‘body’ and his ‘seed’ were very cold.

The confessions also suggest that members of the coven held regular ‘witches’ Sabbaths’: communal meetings with Satan during which they affirmed their allegiance to him and engaged in wild dancing, and occasionally other high-jinx, including trampling all over the crops of one Thomas White at one meeting in 1661. These events generally happened in the dead of night, in various secluded locations in the countryside surrounding Crook of Devon.

It is perhaps worth asking why almost all the accused individuals confessed to these outlandish crimes, since it is probably safe to assume that they were not really witches who had communed with the Devil or cast malevolent spells. Confession was actually extremely common in Scottish witch-trials, and while some people have suggested that the supposed witches might have been suffering from some sort of shared psychosis, or perhaps mass poisoning from ergot fungus, the most likely explanation is much simpler: torture. Technically this was illegal in Scotland, but nonetheless it seems to have been relatively common to force witches to confess by depriving them of sleep. A few days of enforced wakefulness would render the accused people highly suggestible, and might also make them delusional – and therefore willing to agree to whatever scenario their questioners flung at them. The trial documents make no mention of sleep deprivation, which is hardly surprising given its illegality, but it still seems the most likely explanation for the fantastical confessions extracted in 1662.

Conclusion

The Crook of Devon coven was not the only example of Kinross-shire witch-hunting. We know the names of a further sixteen people accused of witchcraft in Crook of Devon alone (all in the early 1660s), and there were also four suspected witches from Kinross and one from Milnathort. But while nothing further is known about these other alleged witches, the survival of our coven’s trial documents means that we can, through these thirteen men and women, trace the mechanics of Scottish witch-hunting in searing, shocking detail. It is a story of fear and anxiety, and of deeply-held beliefs about the tangibility of evil leading to horrendous injustice. Those accused in Crook of Devon were clearly not witches. Instead, they were ordinary folk – perhaps eccentric, perhaps a little socially marginalised, certainly enmeshed in the petty arguments and disagreements characteristic of rural life – who had the misfortune to be swept up in the terrible wave of witch-paranoia that washed over Scotland at the beginning of the 1660s. In 2012, the ‘Witches’ Maze’ was unveiled at Tullibole Castle as a memorial to those indicted at Crook of Devon, a tangible reminder that even the most secluded and out-of-the-way corners of Scotland were not immune from the dreadful tragedy of the witch-hunt.

Further reading

The Crook of Devon trial document are published here: R.B. Begg (ed.), ‘Trials for Witchcraft at Crook of Devon, Kinross-shire, in 1662’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 22 (1887-8), 211-41

C. Larner, Enemies of God: The Witch-Hunt in Scotland (London, 1981)

B.P. Levack, Witch-Hunting in Scotland: Law, Politics and Religion (Abingdon, 2008)

P.G. Maxwell-Stuart, The Great Scottish Witch-Hunt (Stroud, 2007)

J. Goodare (ed.), The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester, 2002)

J. Goodare, L. Martin and J. Millers (eds.), Witchcraft and Belief in Early Modern Scotland (Basingstoke, 2008)

J. Goodare (ed.), Scottish Witches and Witch-Hunters (Basingstoke, 2013)

A version of this article was first published as ‘Bell, Book and Scandal’ in the Kinross Community Council Newsletter (June 2020)

Comments are closed.