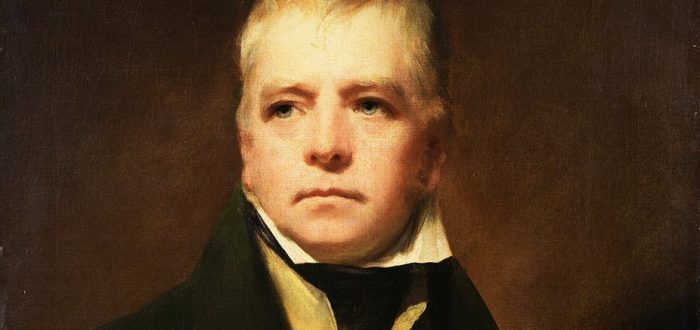

Although the great Scottish writer Sir Walter Scott is most famous as a historical novelist, his work is also notable for frequently exploring supernatural themes. With Halloween just behind us, Dr Daniel Cook delves into Scott’s prose and picks out seven of his spookiest stories.

Follow Daniel on Twitter at @drdanielcook.

Still revered as one of the world’s great historical novelists, Sir Walter Scott kept coming back to the supernatural, the eerie, and the macabre. In The Bride of Lammermoor (1819), most notably, and other historical novels, The Author of Waverley incorporated plot points, tropes and other conventions common to Gothic writing, up to and including the unfinished Calabrian tale Bizarro (1832; first published in 2008). Some of the multivolume novels even include extended, extractable tales of terror: ‘The Fortunes of Martin Waldeck’ in The Antiquary (1816), a Germanic parable about human greed and demonic callousness; ‘Wandering Willie’s Tale’ in Redgauntlet (1824), a Burns-like horror story in Scots; and ‘Donnerhugel’s Narrative’ in Anne of Geierstein (1829), a supernatural take on the cursed marriage plot. While ‘Wandering Willie’s Tale’, above all of Scott’s shorter fictions, has often been included in anthologies of short stories around the world, many of his other Gothic and fantastical short stories have been overlooked. Let’s take a look at seven of his deadliest tales.

‘The Fortunes of Martin Waldeck’ (1816)

Set in the Harz in northern Germany, the story follows a young forester who obtains burning coal from the fire of a demon in order to reignite the furnace that his brothers had allowed to go out. The purloined coal is actually pure gold, which quickly corrupts his integrity. Suffering and death soon follow. The lesson seems simple: greed corrupts. Or perhaps it is: curiosity kills. Or do not be a hero. Unlike most fictional heroes, Martin does not seek a foe (‘the daemon is a good daemon’, he says). In fact, the unnamed inhabitants of the village refuse to hear negative accounts against the daemon from a passing capuchin friar in case they anger it. There is even a suggestion that the villagers admire the daemon as though it were one of them (as a familiar, even famous, fixture of their everyday reality). Leave the demon alone, if you know what’s good for you.

‘Phantasmagoria’ (1818)

In 1818, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine published a bizarre short story in which the banal plot is overshadowed – quite literally – by a supernatural narrator, a sentient shadow who whiles away his days reading books on the occult sciences in his library at the eerie Castle Shadoway, safe from the deadly sunlight that had killed his father. No narrator in literary history seems better placed to deliver a tale of terror – but ‘Phantasmagoria’ is not that story. There is a ghostly prophecy. But it is wholly benign. Even the hero dies peacefully in old age, off the page, after a long military career. Is this a Gothic parody? Or a mockery of the genre’s popularity? Or perhaps it’s a wee experiment in narrative form. In any case, it’s a curious early gem in Scott’s long career.

‘Wandering Willie’s Tale’ (1824)

A masterclass of Burnsian horror, fans of ‘Tam o’ Shanter’ would enjoy this one. Written in Scots, the story follows the travails of the piper Steenie Steenson, Wandering Willie’s grandfather. Steenie, a tenant of Sir Robert Redgauntlet during “the killing times”, when royalist troops were persecuting the Covenanters, goes to pay his overdue rent. Before he receives his receipt, Sir Robert suddenly dies in a gruesome, bloodcurdling manner. Without proof of payment, Sir Robert’s heir demands payment. The despairing Steenie flees to a dark wood where he meets an overly attentive stranger who promises to bring him to the late Redgauntlet for the receipt. Steenie duly encounters his old persecutor, carousing with his dead friends, presumably in hell, and gets what he came for. The hellish scene is shocking enough. But that’s not the end of the story.

‘My Aunt Margaret’s Mirror’ & ‘The Tapestried Chamber’ (1829)

‘My Aunt Margaret’s Mirror’ & ‘The Tapestried Chamber’ (1829)

Read in the unlikely context of the plush Christmas gift book in which the stories eventually appeared, The Keepsake for 1829, ‘My Aunt Margaret’s Mirror’ and ‘The Tapestried Chamber’ repay an audience familiar with the conventions of the supernatural short story. A phantasmagoric tale and a ghost story, respectively, each delivers the core motifs we demand: a magic mirror and a ghost. That said, neither piece is a straightforwardly Gothic work; nor are they miniature parodies or pastiches, as such. If anything, they advocate the mild supernatural strain of the mode, to adopt the phrasing of the first text’s chief storyteller, the eponymous Aunt Margaret. Her magic mirror titillates us, but plot-wise it is redundant. ‘The Tapestried Chamber’ glimpses a ghost of a long-dead murderer, but similarly, her presence is no more haunting than the family painting that captured her evil demeanour while alive.

‘Donnerhugel’s Narrative’ (1829)

One November evening, we hear, Baron Arnheim sat completely alone in the castle’s hall after a day’s hunting, when hasty if trepidatious footsteps assault the stairs. We watch as Caspar, the head of the baron’s stable – ‘terrified to a degree of ecstasy’ – urgently enters the hall. A fiend stalks the stable, he claims, greatly distressed. Finally, after much discussion, the baron investigates. We have long been primed for a demon: we meet a tall dark figure, Dannischemend, who seeks refuge for an entire year. The baron dutifully accepts. We might anticipate some foul deeds now, but no one in the castle could find fault in the Persian Sage (as they dubbed him). The baron and the sage even spend most of their time together, studying. Right on cue, Dannischemend mysteriously flees when the allotted time has passed, perhaps as a consequence of an unknown Faustian pact of some kind. To comfort the baron, the sage tells him that his daughter will soon arrive to continue his lessons. But, he warns, evil will befall the house of Arnheim if Sir Herman treats her as anything other than a teacher. Is it a prophecy or a curse? A divine message or a mundanely paternal warning? Somewhat inevitably, the baron falls in love and marries Hermione. Angered by whispers against his mysterious bride, the baron lets a drop or two of holy water fall on the bride’s forehead, inadvertently killing her. Dismayed and saddened, the guests disperse. A solemn funeral for her is performed. Not all sorceresses are evil – don’t be so prejudiced.

‘The Bridal of Janet Dalrymple’ (1830)

Formally an historical anecdote prefixed to a reissue of The Bride of Lammermoor, this story also looks like a Gothic short – a very short – story. After a brief history of the venerable Dalrymple family, the story rapidly unfolds: Janet has entered a secret engagement. Favouring his own match for his daughter, the father is furious. With extreme reluctance she breaks off her engagement to Lord Rutherford, who angrily curses her. Janet’s wedding with her new fiancé is full of pomp and ceremony but she remains sad and silent. The passage suddenly bursts into a tale of horror. Hearing a shriek from the nuptial chamber, the guests find the bridegroom streaming with blood. The bride, when they can locate her, sits in the corner of a large chimney ‘grinning at them, mopping and mowing’, ‘in a word, absolutely insane’. Two sentences later, she is dead, with no cause suggested. The bridegroom recovers but refuses to give his story. Not long after, he also dies in an unrelated incident, falling from his horse. The full story can no longer be told with any credibility, though many men attempt to explain it away. A family curse or a warning not to mess with true love? You’ve been warned.

Comments are closed.