Dr Alan MacDonald delves into the rich and fascinating papers of Sir Walter Dundas (1562-1636), a West Lothian laird whose innovative land-management practices suggest that ‘Improvement’ may have begun in Scotland a good deal earlier than is often supposed.

Follow Alan on Twitter at @estaitis

Sir Walter Dundas (1562-1636): Pioneer of ‘Improvement’?

When I did my O-Grade History (Standard Grade or Nat 5 for our younger readers), one unit was called ‘Changing Life in Scotland, 1760-1820’ and it included the agricultural revolution. Who can forget James Small’s swing plough, the seed drill, threshing machine, crop rotation, liming the soil to increase yields, and the enclosure movement? Before this enlightened time of scientific advancement, we were told, agriculture was primitive, static, and prone to catastrophic failure. Landlords and tenants stuck to ancient techniques and had no interest in innovation. A key explanation for this was the nature of Scottish society: before c.1700, Scotland was riven with noble feuds and clan warfare. Landed estates were not run for profit because landlords needed to have lots of tenants to maximise the number of fighting men they could call upon. Not until that era of ‘thud and blunder’ was over could they turn their thoughts to commercial estate management.

Changing Interpretations

Historians now favour evolution over revolution when it comes to agricultural change. Scotland before the eighteenth century is no longer seen as a backward, war-torn country, devoid of culture and learning. The Union of Parliaments is not seen as the great turning point in Scotland’s journey to modernity as historians have uncovered the earlier roots of these changes. In the 1990s, the Restoration (1660) was established as the epoch when landowners turned away from military preoccupations after two decades of civil war and occupation. They abandoned grim castles for stately homes surrounded by beautiful gardens, and adopted new techniques of profit-orientated estate management.

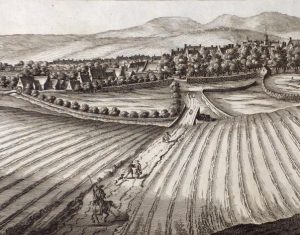

Traditional ‘runrig’ farming in seventeenth-century Scotland.

Then along came another generation of historians, probing further back. They found the shift to prioritising comfortable living over defence was under way before 1600, and showed the nobility to be educated people with an international outlook. Their houses and portraits referenced their traditional role as war-leaders largely to symbolise their ancient lineage. Indeed, the period from c.1580 to c.1640 was one of the most peaceful in Scottish history before c.1750 (considerably more peaceful than the Restoration era).

Since early seventeenth-century landowners were living in comfortable houses, sending their sons to university and filling their libraries with the latest books, perhaps we also need to reconsider how they managed their estates. There is, however a snag. Detailed records of estate management are frustratingly scarce.

Sir Walter Dundas of that Ilk

Fortunately, in the papers of the lairds of Dundas, there is a treasure trove of rentals, accounts, and records of crops sowed, harvested, and stored. These allow us to piece together how a medium-sized estate in West Lothian was run at the beginning of the seventeenth century.

Sir Walter Dundas of that Ilk, having attended the University of St Andrews in the 1570s, inherited the estate in 1598 in his mid-thirties. He was an avid buyer of the latest books, with a library packed with classical literature, philosophy, theology and political treatises. He was also a keen and active manager of his estates. Aided by a series of good harvests in the 1610s, which allowed him to sell considerable quantities of surplus cereals, he set about investing in substantial estate improvements.

He began with work on his house and its immediate surroundings, adding a large walled garden with pavilions at its four corners. These buildings (also known as ‘banqueting houses’) provided intimate spaces for entertaining visitors to his garden, which he also adorned with an elaborate fountain-cum-sundial almost 4m high. But he did not stop there, for once the ‘gairden work’ was completed, he set the masons to creating ‘the park’, a substantial enclosed field. At first it held his new oxen, bought in for ploughing, but before long he was growing wheat there. Soon it became known as ‘the north park’, for other enclosures were also built. This was real innovation, the beginnings of the shift from the ‘open field’ system towards the now familiar patchwork of enclosed fields, a change previously attributed to the Restoration period.

The ornamental fountain in Dundas’ garden.

Increased crop yields were achieved through the extensive addition of lime to the soil. Lime makes it easier for plants to take up nutrients, and Sir Walter was fortunate to have limestone on his estate. He constructed kilns to process it for his own use and for sale to others. An account book from the 1620s shows he made almost £2,000 from the sale of lime in just two and a half years, over and above what he kept for his own use to extend the area under cultivation by converting rough pasture to arable. Unsurprisingly, he also spent considerable sums constructing a new barn for storing the growing quantities of cereals his estate was producing.

Were these innovations widespread?

So, was Sir Walter a pioneer or simply doing what everyone else was up to? The answer is, we don’t know yet. There are indications that similar things may have been going on elsewhere. Extensive liming across the Lothians is noted in a series of parish reports on agriculture produced in the later 1620s. These also record the existence of enclosures. Further research in estate archives is needed before we can get a clear picture, but it would have been surprising if Sir Walter’s neighbours hadn’t been doing the same things. Landlords were well-connected, as well as well-read. They shared in local administration, visited each other and corresponded regularly. They were familiar with the latest ideas from England and the Continent and wanted to show off their fashionable taste. Nowhere in Sir Walter Dundas’s personal accounts is there any reference to spending on arms or armour, or on making his house defensible. Instead he spent his money on books, clothing, wine, beautifying his house and gardens, and improving his estate: the fountain he built bears a Latin inscription which speaks of ‘the pleasure and enjoyment of spectators’ and ‘the kind and welcome friends of the host’.

Comments are closed.