Sylvia Valentine is a professional genealogist who is also completing a PhD at the University of Dundee. Her thesis explores opposition to compulsory smallpox vaccination in 19th and early 20th– century Scotland.

Follow Sylvia on Twitter at @historylady2013

One of the least recognised figures in the history of smallpox prevention is Aberdonian Charles Maitland, the surgeon who performed the first inoculations for smallpox both in England and Scotland. He died in Aberdeen on 28 January 1748 and was interred in Methlick kirkyard on 7 February. According to the memorial inscription he was buried in the same grave as his parents Patrick Maitland, late of Little Ardoch, (Little Ardo) and Jean Robertson, and several of his siblings.

Little is known about Charles Maitland’s family. He was aged about 80 at the time of his death, but it is not possible to pinpoint his birth or baptism as the baptismal records for the relevant period, around 1666-68 are missing.

Obituaries in both the Aberdeen Press and Journal of 9 February 1748 and the Caledonian Mercury (15 February 1748) described his wealth and benevolence. He was estimated to have been worth £5,000 (approximately £770,700 today), ‘a fortune acquired by his own endeavours’. The Caledonian described him as ‘a gentleman justly esteemed by those who knew him’. He left his estate to friends and relations, and also endowed a charity in the parish of his birth, Methlick, by means of a heritable bond, valued at 6,000 merks Scots (a merk being equivalent to two-thirds of a pound).

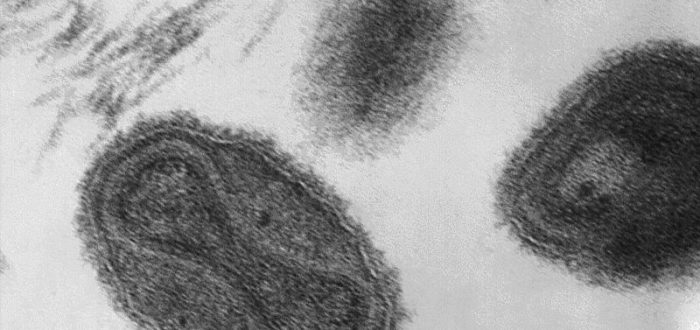

Maitland became surgeon to the British ambassador to Turkey in 1717 where he inoculated the ambassador’s son, at the behest of his wife Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who later championed the cause of inoculation in England. A few years after their return from Turkey in 1721, she asked Maitland to inoculate her daughter Mary during a smallpox epidemic in London. The following year Maitland inoculated six people in Aberdeenshire, but one died, making the procedure unpopular in the county. Inoculation was not without risk. It used lymph from an infected person which then infected the patient. It depended on the skill of the inoculator to recognise that the lymph provider was infected by the milder version of smallpox, variola minor, rather than variola major, which had a higher mortality rate.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, by Jonathan Richardson the younger

Maitland is known to have inoculated approximately 80 people in England and in April 1722 was involved in the inoculation of the Princesses Amelia and Caroline at the command of the Princess of Wales. He subsequently inoculated their brother Prince Frederick in Hanover in 1724. One newspaper obituary said he was ‘an excellent surgeon and famous for inoculating the smallpox, and was handsomely rewarded for inoculating Prince Frederick’. Maitland was paid £1,000 from the privy purse.

Maitland also inoculated the children of medical men and aristocratic parents. Among them was Dr James Keith, one of the three physicians who attended to witness the inoculation Mary Montagu. Keith had lost all but one of his children to smallpox and was sufficiently convinced by the procedure to have Maitland inoculate his surviving son Peter. Keith was a fellow Aberdonian and has been identified as a fellow student of Maitland at Aberdeen University, although it has not been possible to categorically verify this. Keith also made Maitland a trustee and guardian of Peter in his will.

Before the princesses could be inoculated however, an experiment was conducted on six condemned prisoners incarcerated in Newgate Prison, who were promised pardons in return for being inoculated. According to the account of Sir Hans Sloane written some years after the event and eventually published in Philosophical Transactions, initially Maitland was reluctant to perform the inoculations, and it was only after Sloane spoke to him, that he agreed to do so. The experiment was widely reported in the press at the time, including by the Caledonian Mercury and Newcastle Courant newspapers amongst others. The experiment was considered to be a success and the prisoners were duly reprieved and pardoned. Although Sir Hans Sloane reported favourably on the experiment, the Princess of Wales remained a little hesitant. A further experiment was conducted in late February 1722, when the guinea pigs were orphan children from the parish of St. James Westminster. Maitland performed the inoculations, and according to Sloane, the experiment was also deemed to be a success. Following the experiments, the inoculation of the princesses Amelia and Caroline went ahead.

Princess Amelia, by Jean-Baptiste van Loo

Charles Maitland had connections both to the British aristocracy and leading members of the medical profession. He was a pioneer, bringing inoculation from Turkey to a wider, if affluent, public in England and Scotland, at a time when many English physicians considered this foreign procedure practiced by old women as an amusing diversion, unworthy of their consideration. Before Edward Jenner made connections between smallpox and cowpox and cowpox lymph became the much safer vaccine of choice, inoculation was the measure which provided protection against the much-feared disease.

In 2010, Anita Guerrini observed that Charles Maitland was a candidate for the most important figure not to appear in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, surely something that needs correction.

Further reading

Ian Glynn and Jenifer Glyn, The Life and death of Smallpox (London, 2004)

Genevieve Miller, The Adoption of Inoculation of Smallpox in England and France (Philadelphia, 1957)

Peter Razzell, The Conquest of Smallpox (Firle, 1977)

J.R.Smith, The Speckled Monster (Chelmsford, 1987)

Gareth Williams, Angel of Death, The Story of Smallpox (Basingstoke 2010)