Dr Allan Kennedy explores ideas and practice around the use of judicial torture in early modern Scotland.

Follow Allan on Twitter at: @Allan_D_Kennedy

When we discuss crime and punishment in the past, we often instinctively think about torture. Grisly images of broken, brutalised bodies worm their way into our imaginations, especially when we’re thinking about Scotland, whose judicial system is popularly assumed to have been particularly bloodthirsty. In reality, however, the use of torture in Scottish History has been much more limited, and much more controversial, than we might expect.

The use of torture

While there are some suggestions that torture was used during the Middle Ages – the assassins of King James I (d.1437) may have undergone it, for example – the ‘golden age’ of judicial torture in Scotland was the early modern era, and in particular the 17th century. But even during this period, its use was heavily regulated. In order to torture a suspected or convicted criminal – or at least, in order to do so legally – you needed to have a specific warrant from Parliament or the Privy Council. And these were rarely granted: between 1591 and 1708, only 39 warrants were issued, covering fewer than 50 individuals.

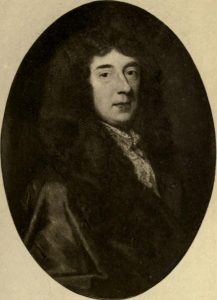

Why was torture so comparatively rare in Scotland? In part, no doubt, it was to do with exactly the same ethical qualms that animate people today – although, given how ready the Scottish judicial system was to inflict vicious physical punishment on criminals, this should not be pushed too far . More pertinently, the authorities were often sceptical about how effective torture was as a judicial tool. As George Mackenzie of Rosehaugh, a prominent late-17th-century lawyer and twice Lord Advocate, put it: ‘Some obstinat persons do oftentimes deny the Truth, whilst others who are frail, and timorous, confess for fear, what is not true’. The ineffectiveness of torture was particularly stark, Rosehaugh and others felt, when it was being used to extract confessions, the evidential value of which was widely regarded as suspect.

George Mackenzie of Rosehaugh, by Godfrey Kneller

If judicial torture was felt to be so problematic, why was it used at all? We can get a good sense of this from considering one case from 1680, when two men, John Spreull and Robert Hamilton, were put to torture. They were accused of plotting to murder the king, Charles II, and in particular the government was looking for answers to three questions. One: who had recruited them into the plot? Two: did the plot herald a coming rebellion? And three: Who were their co-conspirators? What the torturers were not asked to do was to extract confessions from Spreull and Hamilton, and indeed the government was at pains to point out that they were being subjected to torture only after they had freely confessed to involvement in the plot. What this case neatly reflects is that torture was generally seen not as a means of solving crimes, but as a tool of last resort for uncovering urgently-required information, to be used only when weighty matters of state or security were at stake. In that sense, torture in Scotland was less a judicial tool than a political one.

Judicial torture was particularly associated with the Restoration (1660-89), a period during which concerns about order and security, not least in the face of Presbyterian opposition, were especially acute. Indeed, torture was listed as one of the ‘grievances’ justifying the deposition of James VII in 1689, and it seems to have been used rarely, if at all, thereafter. The practice was formally outlawed as part of the Treason Act, passed by the British Parliament in 1708.

Methods of torture

Torture thus had a limited, highly-regulated place within the Scottish judicial system. But what did it actually look like in practice? Anybody who has visited a place like the Edinburgh Dungeon will be painfully familiar with all the weird and wonderful methods of torture that governments of the early modern period came up with: water torture, strappado, stretching on the rack, nail-removal, rat torture – the list is a long one. In Scotland, though, torture, on the rare occasions it was sanctioned, was rather less theatrical, with two devices predominating. The first, and marginally less terrible of these, was the thumbscrews, or as they were sometimes known in Scotland, the ‘thumbikins’. This form of torture generally involved trapping the victim’s thumbs in a vice and then slowly tightening it, squeezing and, eventually, crushing both digits. The precise design of thumbscrew apparatus could vary widely, but the basic principle remained the same, providing a simple but very effective means of inflicting pain.

Examples of Scottish thumbscrews (David Monniaux / CC BY-SA (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)

The thumbscrews were ghastly. But they were as nothing compared to the second of Scotland’s characteristic torture devices, the Boot. There were countless variations on this torture throughout Europe, but the version favoured in Scotland, sometimes known as the ‘Spanish Boot’, involved two phases. Firstly, the victim’s lower leg was placed in a tight, stiff sheath, usually made of metal or wood, which completely encased the leg, much like a boot – hence the name. In the second stage, wedges of wood were hammered into the space between sheath and leg, lacerating the flesh and, ultimately, breaking or crushing the bones. The Boot tended to be used against especially dangerous criminals, with a good example being the bandit leader Patrick Roy MacGregor. MacGregor has run riot in the Banffshire area during the 1660s, stealing, pillaging, killing and generally causing mayhem prior to his capture in 1667. Once he was in its hands, the government promptly put him through two episodes of torture-by-Boot, partly to extract a confession, but more particularly because they wanted to find out who his accomplices were. Needless to say, MacGregor broke under the pressure of the Boot, admitting his guilt and naming the Earl of Aboyne as his chief sponsor. For MacGregor, as no doubt for many of the other unfortunate Scots forced to wear the Boot, this was a form of torture well-placed to loosen even the most stubborn of tongues.

There was one more method of torture commonly used in Scotland, but it needs to be treated separately from the first two. The thumbscrews and the Boot were formal, government-sanctioned mechanisms. On occasion, however, torture was imposed unofficially, and therefore illegally, by people working with the more local courts or even with Church authorities. To get away with that, you had to make sure you used a method that could go undetected and which was deniable, and that mostly, although admittedly not exclusively, meant sleep deprivation. Not letting a prisoner sleep for days on end was an especially favoured means of extracting confessions from suspected witches; we know, for example, that a group of reputed witches in Pittenween in 1643 were ordered by the local kirk session to be kept perpetually awake with a view to making them admit their witchcraft. The association between sleep deprivation and witchcraft largely came about because of the procedural oddities of witch-prosecution in Scotland – put simply, you usually could not prosecute a witch without special leave from central government, and you generally could not get such licence unless you already had a confession. Sleep deprivation was a method of securing the necessary admissions of guilt, but which was easily deniable after the fact and which could be argued, albeit tendentiously, not to constitute ‘torture’ at all. Sleep-deprivation probably helped inflate the size of the Scottish witch-hunt, especially during the huge panic of 1661-2, but it also contributed to the decline of witch-prosecutions: the knowledge that confessions were often extracted under torture was one of grounds upon which the government became increasingly reluctant to sanction witch-trials from the mid-1660s onwards.

Conclusion

Where, then, does all of this leave us in terms of understanding torture in Scotland’s past? In many ways this was a minor aspect of the Scottish judicial system, imposed rarely, and exclusively on especially dangerous individuals. Mainly its role was to secure intelligence and information, rather than to extract a confession. Perhaps because of the relative scarcity of its use (or at least, of its formally-sanctioned and recorded use) torture in Scotland never quite reached the heights of sensationally creative cruelty that it attained in parts of continental Europe – although that is certainly not to deny the horrors of both the thumbscrews and the Boot, or, indeed, of the subtler but equally unpleasant art of sleep-deprivation. None of this implies that Scots in the past were unusually gentle or squeamish. But it does mean that we have to be careful before jumping to the conclusion that justice in the past was simply a question of brutalising those accused of crimes. The system was rather more sophisticated than that, and so, while we can shake our heads as the use of torture in Scottish History, we should always remember that it was never a central, nor even a particularly important part of the story.

Further reading

Stephen J. Davies, ‘The Courts and the Scottish Legal System 1600-1747: The Case of Stirlingshire’ in V.A.C. Gattrell, B. Lenman and G. Parker (eds.), Crime and the Law: The Social History of Crime in Western Europe since 1500 (London, 1980), 120-54

Clare Jackson, ‘Judicial Torture, the Liberties of the Subject, and Anglo-Scottish Relations’ in T.C. Smout, (ed.), Anglo-Scottish Relations from 1603 to 1900 (Oxford, 2005), 75-102

Brian P. Levack, ‘Judicial Torture in the Age of Mackenzie’, in H.L. MacQueen (ed.), Miscellany IV, Stair Society (Edinburgh, 2002), 185-98

George Mackenzie, The Laws and Customs of Scotland, in Matters Criminal (Edinburgh, 1678)

Comments are closed.