Dr Allan Kennedy discusses the concept of uncleanliness in early modern Scotland, and explores the way this idea linked to issues of public order and criminal deviance.

Follow Allan on Twitter at: @Allan_D_Kennedy

Among the many consequences of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic has been renewed emphasis on the importance of cleanliness. Thorough hand-washing, we are told, is one of our key weapon in the fight against disease. Such advice is of course rooted in science, but it also taps into a deep-rooted cultural distaste for dirt. And, as the case of early modern Scotland shows, this means that ‘dirtiness’ can provide a framework for understanding, and responding to, all sorts of other threats.

Cleanliness and the environment

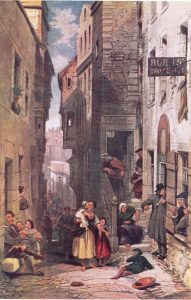

A depiction of the often grimy environment of early modern Edinburgh. By George Cattermole

Despite our tendency to assume that all people in the past were intensely relaxed about dirt and muck, early modern Scots often demonstrated a thoroughly recognisable horror of filth. Partly this was because it was simply unpleasant, but there was also a sense that an unclean environment was dishonourable; thus, when the Scottish Parliament in 1618 heard a complaint against butchers and candle-makers in Edinburgh, it was claimed that their activities produced such quantities muck as to render the town ‘detestable in the sight of strangers’ and make them think it ‘a puddle of filth and filthiness’. At the same time, dirt was recognised as unhealthy, so that a common response to outbreaks of plague was to send in ‘clengears’ to clean and disinfect the stricken area, as was, for example, done in Stirling in 1607.

In consequence of all this, early modern communities, particularly towns, were often deeply concerned with improving environmental cleanliness. Take, for instance, the small northern burgh of Inverness, whose council between 1668 and 1682 alone issued ordinances for the clearing of middens (twice), the culling of ‘curr dogs’, and against the ‘harm and prejudice’ occasioned by transportation of ‘muck or dung’ across the local bridge. Drives like this were replicated across the country throughout the early modern period, and they make it clear that Scots were deeply concerned about avoiding the deleterious effects of over-exposure to muck.

The filthiness of sin

This horror of dirtiness found figurative expression as well. After the Reformation, Scots became very comfortable using the language of uncleanliness in connection with sin. The poet Elizabeth Melville articulated this idea eloquently in her early-seventeenth-century work A Godlie Dream:

What can we do? We clogged are with sin,

In filthy vice our senseless souls are drowned.

Though we resolve, we never can begin,

T’amend our lives, but sin doth still abound.

Here, sin is conceptualised as befoulment, a literal stain on the soul. Moreover this filth, if left unchallenged, has the potential to cause irreparable corruption. As with the physical world, so with the soul: uncleanliness could destroy you.

But if any and all sins could be understood in terms of dirtiness, the concept increasingly came to be associated with two broad classes of deviant behaviour in particular. The first of these was serious crime, in connection with which such language came to denote an unnatural breach of societal or behavioural norms. Thus, the alleged collaboration of the Earl of Morton in the murder of Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley (second husband of Mary, Queen of Scots) was in 1584 described as ‘filthy’. In cases like this, crime became a metaphorical stain to be expunged. It is no coincidence, therefore, that suspected criminals who were acquitted at trial were not in Scotland descried as ‘innocent’ of the charges, but as ‘clean’ of them.

Still more firmly rooted in the language of uncleanliness were sexual misdemeanours. Policing of deviant sex, mostly through the local structures of the Church, was extremely rigorous in early modern Scotland, and in recording vices like fornication and adultery, words like ‘filthy’, ‘vile’ and ‘foul’ were used liberally. It is also telling that offences like these were typically punished with an order for public repentance, such as standing in sackcloth or sitting on the ‘repentance stool’. These were mechanisms by which the dirtiness of the deviant acts would be metaphorically cleansed not just from the person(s) committing them, but also from the wider community of which they were part.

Witchcraft, from Newes from Scotland (1591)

More serious sexual offences, like sodomy, bestiality, and incest, were even more strongly associated with befoulment, and this was reflected in the unique punishments habitually attached to them: the guilty parties were cremated after execution. This, of course, denied them the comfort of resurrection, but it also worked to expunge any trace of the filthiness their crimes had brought into the world. Similarly, animals involved in bestiality were routinely slaughtered and burnt, not because they were regarded as sharing guilt, but simply, in the words of the 18th-century legal scholar William Forbes, ‘for abolishing the memory of so horrid a wickedness’.

Underlying fears about dirtiness of the soul were however at their most intense when Scots were confronted with one phenomenon in particular: witchcraft. This was, from one perspective, a terrible crime, since it involved using occult means to achieve unnatural power over other members of the community. But it was also a sexual crime: witches, after all, were routinely assumed to have acquired their power following copulating with the Devil. Witches were thus living embodiments of the way that deviant sex could introduce filthiness into the human body, befoulment that could then spread out to infect the society around them.

Conclusion

While people in early modern Scotland clearly led lives marked by far higher levels of uncleanliness that people today would deem acceptable, they still regarded dirt as unpleasant and unhealthy, and they did make efforts to minimise it. This innate distaste for muck is what made the concept an appealing prism through which to understand the problem of vice. By using the language of uncleanliness when speaking about criminals, sexual deviant and witches, Scots demonstrated that the understood sin as a metaphorical form of dirt, as a stain that besmirched the soul and threatened irreparable befoulment if left to its own devices. That, in turn, made it necessary to take decisive action – collectively and individually – to cleanse a spiritual stain whenever one was detected. Equating sin with dirt therefore spoke to the kind of active, demonstrative piety that characterised post-Reformation Scotland, and which was to prove so important in shaping all aspects of Scottish life right up to the modern age.