Samantha Hunter is a first-year PhD researcher at the University of Dundee, exploring governance and control in seventeenth-century Scotland. In this guest post, she discusses early modern expectations of church attendance, and asks when, and for what reasons, certain people might have been excused from attending.

Follow Samantha on Twitter at @sam_hunter95

It is often assumed that, due to the power and presence of the Church in early modern Scotland, everyone was expected to attend church services at all appropriate times. Absences could be excused for travel, although generally only if people away from home attended services at their destination and were only away for no more than a couple of days. Sickness, too, could sometimes excuse non-attendance: in Auchtermuchty, Helen Myllar was forgiven her absences from both the kirk and the communion due to her ‘long and heavie sickness’ in July 1649. Yet these are not the only reasons that absences could be excused, and indeed, in some cases, even expected.

Absences and punishments

A set of jougs at Oxnam parish kirk, by Walter Baxter

Absenting from church services was not received well if the individual did not have a good explanation for their actions. For first-time offences or a single instance of missing a service, the individual would usually have been told off in front of the members of the kirk session – and occasionally the whole congregation. Those who were repeat offenders often faced more severe repercussions for their transgressions, with some having to pay fines and others facing time in the jougs. This was an iron collar attached to a wall or a pillar that would be placed around the individual’s neck. They would remain there for a couple of hours at the very least. These jougs were located where the offender would be seen by the community as a means of public humiliation for their actions, but the procedure was also to demonstrate to the rest of the community what fate may await them if they committed a similar transgression. For his long absenting from the kirk and refusing to reconcile a personal feud, Henrie Sime of Auchtermuchty was not only suspended from his office as an elder but also debarred from the communion for more than 15 months. These punishments were deemed necessary because attendance at sermons was a fundamental ideal in reformed Scotland. The teachings and practices outlined in sermons were necessary to allow parishioners to fulfil their potential to be good Christians and protect the overall well-being of the community from scandalous or dangerous behaviour.

Expected congregations

So, if it were necessary that everyone was to hear the sermons and receive the teachings from the minister, how might this be done for those who could not attend the services? As already stated, there were acceptable excuses for absence for the likes of sickness and travel, but these were not the only obstacles that could prevent someone from attending their local services. With sickness comes the need for nursing and care. Age and severity of illness had a large role to play as to whether an individual needed constant care. For example, a typically healthy adult who had come down with a case of the flu would be unlikely to need constant supervision and could be left at home to recover while the rest of the household attended services. The elderly and the young, however, would be the ones to need a more constant presence tending to them. Both groups would have become much more vulnerable during these times. While there was some aid to be found in the parish through relief funds for sick individuals unable to work, it was very much the responsibility of the family to provide care for their relatives.

An example which involves both unacceptable and acceptable absences can be found in Dairsie, Fife. In August 1649, Hellen Ramsay had been summoned before the kirk session to carry out an act of repentance due to her having frequently missed services in the July. Although not explicitly stated, one cause for her absences may have been due to her being in the late stages of pregnancy and having two other young children at home. Her absences would have earned her a summons and required her to carry out an act of repentance. Although convicted and sentenced, the session took her condition into account and delayed the date of this repentance until December, three months after her child had been born. When December arrived, Hellen did not appear before the session and her apologies were made by her husband who stated that she had remained at home to care for her two young and ‘extremelie diseased and sick’ children, promising to make her repentance as soon as she was able. The session was aware of the condition of the children and so were satisfied that her excuse was valid. As it turned out, it would be March 1650 before she was able to appear in person.

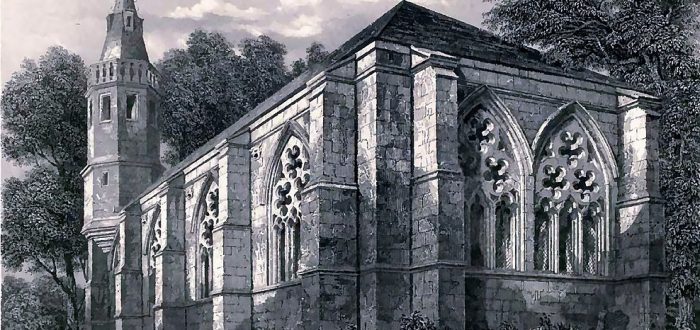

Pittenweem parish church, by Kim Traynor

But it is not just illness that prevented certain groups from attending services. The very fact that they were children was reason enough to put rules in place about church attendance of the young. In Pittenweem in 1655, the kirk session declared that children were expected to attend services every Sunday ‘providing they bee paste 7 or 8 years’, presumably the age at which children were deemed old enough to know how to behave themselves during services.

The parents or guardians of those deemed too young to attend church were instructed to keep them at home or indoors to prevent them playing outside and creating noise in the vicinity of the church, disrupting the service inside. This implies that there must often have been certain members of the community who were acknowledged to be appropriately excused from attending every service because of childcare duties, whether as parent, grandparent, or even an older sibling.

It consequently fell to the head of the household to ensure that all within the family were properly instructed in the lessons and sermons of the day. To make sure this was carried through, the individual may have been asked by the minister or one of the elders at a later date what they had learned or perhaps carry out a recitation. The private home acted as a smaller representation of the kingdom on the whole. The behaviours of the individuals within a family could have great impacts on the ability of the town to achieve this ideal of Christian wellbeing and community. As Susan Amussen noted, ‘[w]hat happened in the household was important for the village, the county, and ultimately the state’. Just as ministers and kirk sessions were responsible for ecclesiastical wellbeing and discipline, and as magistrates were responsible for civil sphere, the head of the household was responsible for familial sphere.

Conclusion

The assumptions that everyone in the early modern period had to attend church services or face hefty consequences only reveals part of the story. While it is true that there were many who willingly chose to absent themselves from the services without a good excuse that was accepted by the kirk session, the chances of them doing so without consequence were very slim indeed. Even those who claimed illness were sometimes asked to provide evidence of their affliction before their absence would be accepted. But kirk sessions also recognised that the very old, the very young, and the chronically sick could not be required to attend, and that, moreover, such people were likely to have caregivers who could similarly be excused – so long as alternative instruction could be provided through networks of family and community. What this demonstrates is that the Church of Scotland during the seventeenth century was not some intrusive, militant entity that set out to make the lives of parishioners difficult or unpleasant for the sake of it. The fundamental ideas of community wellbeing and true Christian behaviour were most effectively instilled during service attendance, yet there was room for flexibility when it was required.

Further reading

S.D. Amussen, ‘Punishment, Discipline and Power: the Social Meaning of Violence in Early Modern England’, Journal of British Studies 34:2 (1995), 1-34.

C. Langley, ‘Lying sick to die: Dying, informal care and authority in Scotland, c. 1600-1660’, Sixteenth Century Journal 48:1 (2017), 1-26

C. Langley, ‘Caring for soldiers, veterans and families in Scotland, 1638-1651’, History: The Journal of the Historical Association (2016), 5-23

J. McCallum, ‘Charity and Conflict: Poor Relief in Mid-Seventeenth-Century Dundee’, Scottish Historical Review 95:1 (2016), 30-56

M. Todd, The Culture of Protestantism in Early Modern Scotland, (New Haven, 2002)

Comments are closed.