Dr Allan Kennedy explores what life was like for the Scottish women who made their homes in London during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

Follow Allan on Twitter at: @Allan_D_Kennedy

Since 2018, I, in collaboration with Professor Keith Brown (University of Manchester) and Dr Siobhan Talbott (Keele University), have published a series of articles about Scottish migration to early modern England, focused on the period 1603-c.1760. Much of this work, however, concentrated heavily on Scottish men. As we will see below, there are methodological reasons for this gender-bias, but it has had the deleterious effect of privileging the male over the female experience. And that is deeply problematic, not only out of principle, but also for intellectual reasons: there were lots of Scottish women in early modern England, and ignoring their voices blinds us to a significant part of the story. In this post, therefore, I want to let some of these voices be heard by focusing on one part of England in particular – namely London – and from this basis to ask what was distinctive about the female experience of being a Scot trying to make a life south of the border.

Where were Scottish women?

In general terms, Scottish women are far more difficult to trace in the sources than Scottish men. Often their identities are subsumed within those of the men around them, principally husbands and fathers, meaning that they become essentially invisible. Nonetheless, they can be found, even if the traces that remain are often frustratingly vague. Take, for example, Barbara Marshall, who appeared as a witness before London Consistory Court in 1702. From this record, we know that Barbara was Scottish, 26 years old, and married to a mariner. We also know that she had been living in St Johns, Wapping for at least ten years – that is, since 1692 at the latest. But beyond this barebones outline, we can glean nothing further about Barbara. Why did she leave Scotland? Did she have any children? What was her job, if she had one? What happened to her after 1702? None of these questions can be answered, and they exemplify the frustrations involved in trying to reconstruct the experiences of Scottish women in early modern England.

Nevertheless, we can scrape together enough information to suggest that Scotswomen could be found just about anywhere in early modern England: Glaswegian Elizabeth Lawry, for example, turned up as a vagrant in Lostwithiel in 1761, about as deep into England as it is possible to get. In common with Scottish men, however, female Scots tended to cluster in a few parts of England in particular. The northernmost counties – Cumberland, Yorkshire, and especially Northumberland – were popular, but easily the biggest migration-magnet was London. The capital accounted for around 34% of the named women captured in the recent ‘Anglo-Scottish Migration’ project at the University of Manchester, making it the most common destination for Scottish women (the next-most-common, Northumberland, accounted for just over 20% of the total). This is hardly surprising, since London was in the early modern period beginning to emerge as a global metropolis, and was busily proving it capacity for absorbing migrants from throughout the British Isles, and indeed far beyond. It is clear that London was the primary destination for Scottish men moving to England, and the information we have, limited though it is, suggests that the same was true for women.

Occupations

Princess Elizabeth at age 7, by Robert Peake the elder.

But if Scottish women could certainly be found in early modern London, what was their typical profile? Opportunities for migration and settlement were perhaps greatest for elite women. None, of course, were more elite than Dunfermline-born Princess Elizabeth, the later ‘Winter Queen’ of Bohemia, who followed her father, James VI, to London after he inherited the English throne in 1603. There were other women, such as Mary Stewart, wife of James’s favourite Sir Roger Aston, for whom the relocation of the court necessitated settlement in London, but more usually, elite women were drawn to the capital through marriage. Take, for instance, Anne Scott, daughter of Francis, 2nd earl of Buccleuch. Born in Dundee in 1651, she made the move to London in 1661 in order to marry Charles II’s illegitimate son, James Scott, duke of Monmouth. Marriage ties like this quickly ensured that some women of the Scottish aristocracy, particularly among its more Anglicised families, were in fact born in London. One early example was the formidable Anne Hamilton, 3rd duchess of Hamilton, who spent most of her life at Hamilton Palace, but entered the world at the Palace of Whitehall in 1632.

Of course, only a tiny minority of the Scottish women who ended up in London were aristocrats. For those lower down the social scale, livings had to be made in some other way. A significant proportion of male migrants earned their money in skilled or professional trades. Legal and social constraints meant that this occupational route was far less open to women, but it was clearly not closed entirely. Barbara Molleson and Jane Falconer, both of Aberdeen, entered as apprentice drapers in 1702 and 1703 respectively, both serving the same master, fellow-Scot Gilbert Molleson, suggesting that ethnic and, perhaps, family relationships could open up unusual opportunities. But there were other female apprentices in the capital: Mary Young of Edinburgh began training as a founder in 1681, while Jennet Bell, also of Edinburgh, was taken on by a stationer (interestingly another women, Martha Jole) in 1747. It is not clear if any of these women completed their apprenticeships, let alone went on actually to ply their chosen trades, but the very fact of their entering as apprentices at all suggests that artisanal work was at least possible for Scottish women.

There were probably many more women working in less regulated trades; people like Jane Forest, who worked as a flax-spinner between c.1690 and 1710, or Isabella Bowman, a merchant operating near the Hermitage around 1750. Others set themselves up in hospitality. Catherine Thompson arrived in London around 1713, when she and her husband began operating an alehouse called The Thistle and Crown in Marigold Court, although the venture apparently failed after a year or so.

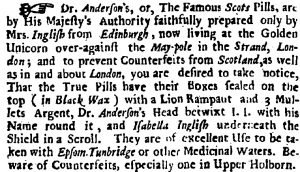

One of the most intriguing examples of a Scotswoman in a trade was Isabella Inglish. She was an apothecary who relocated from Edinburgh to London some time around 1700, and who manufactured a cold medicine known as ‘The Famous Scotch Pills’. From her shop in The Strand, Inglish sold her pills in small boxes sealed with black wax and stamped with a Lion Rampant, continuing in business until at least 1715. Inglish is known only through newspaper advertisements for her medicine – perhaps she was not even a real person, merely a marketing construct. But real or fictional, she is emblematic of the space available in early modern England, or at least London, for Scottish women to carve out independent economic identities.

Advert for Isabella Inglish’s medicine, from the Flying Post or The Post Master, 26 November 1715.

Increasingly, however, the most common work for Scottish women relocating to London was domestic service. As an example of this, we might look at Ann Hayes. She moved to London around 1688, at which point she must have been at least in her mid-teens, because she soon got married to a Dutchman (or possibly a German) named William. He died soon thereafter, and so Ann went into domestic service. She seems to have spent most of the next three decades circulating between a succession of masters as a yearly hired servant. In 1717, however, she was hired by James Scott in Vine Street as a live-in servant. She remained with him for ten years, until she was at least in her mid-50s, earning an annual wage of 50 shillings, plus food and lodging. The length of Anne Hayes’ working life probably made her unusual among domestic servants, but nevertheless she demonstrates how this could be one of the most reliable ways for migrant women to support themselves once they arrived in London.

Women in trouble

Work of the kind outlined above was largely, though not exclusively, the preserve of young and/or single women. Once they got married, most women would have been expected to give up their jobs, and even if they continued working, this would probably remain hidden from us thanks to the problem of identity-erasure mentioned above. When they become visible again, it was often because they were widowed: this was for instance the sole designation given to London-based Jeane Trotter when she proved her will in 1635.

But widowhood, in removing the economic support provided by a husband, carried significant dangers. Jane Sinclair was the wife of joiner John Sinclair, whom she married in Edinburgh around 1754. The pair moved to London shortly thereafter, presumably surviving through John’s trade, but he died at the start of 1758. By November, Jane had been apprehended as a vagrant by the authorities of St Margaret’s, Westminster. A similar trajectory was often followed by soldiers’ wives, who could rapidly slip into destitution when their husbands were posted overseas. This was what happened to Ann Flew, of the Scottish settlement of ‘Collinabine’, who was apprehended for vagrancy in 1742 while her husband was on active service in Flanders during the War of the Austrian Succession. Men, however, could occasion a women’s descent into vagrancy even without committing to marriage. Catherine Smith, a 27-year-old Shetlander, was sent to the workhouse of St Martin in the Fields in 1752 because she had conceived an illegitimate child with the soldier Thomas Steuart. The baby, a boy, had been delivered in a grocer’s shop on The Strand, with the proprietor himself, a Mr Trim, acting as midwife!

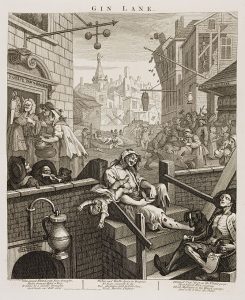

Gin Lane, by William Hogarth. A contemporary conception of female degeneracy.

Vagrancy was not the only form of deviance into which Scottish women might slip: some lived lives of crime. Jane Bowman left Scotland at the age of twelve, and after living for several years in Durham, arrived in London in the mid-1690s. The reasons for her southward movement are unknown, but she seems to have supported herself largely through crime, eventually leading to her arrest and execution for prostitution in 1703, still aged only 26. Only two years later, another young Scotswomen, Jane Dyer, similarly met her end at Tyburn. Not yet 25, she claimed to have indulged in ‘all Sins, Murther excepted’ during her short life, and indeed had already been branded for some earlier felony by the time of her final arrest for theft. Cases like Bowman’s and Dyer’s are a reminder that, while most Scottish women in early modern London seem to have lived fairly mainstream lives, there was a minority for whom the experience of moving south of the border was dominated by marginality, deprivation, and criminality.

Conclusion

In the study of early modern migration, women are often assumed to have exercised little agency, cast as hangers-on to the men in their lives. And certainly, some of them seem to have conformed to this pattern – women like Marione Monro, wife of Reverend Alexander Monro, who followed her Episcopalian husband to London to escape the ‘Glorious’ Revolution in the 1690s. She remained in London, first as wife and then as widow, until around the 1720s, but seems never to have built an independent life, instead melting in the households of her husband and, latterly, children. As a Scotswomen in London, it was possible more or less to disappear.

But, as this post has tried to show, not all women were mere bystanders in essentially male stories. While the opportunities available to them were more limited than those on offer to Scottish men, it was nonetheless possibly for them to find a role in London, be it as landlady, artisan, skilled worker or, especially, domestic servant. The metropolis presented hazards too, however, so that slipping into vagrancy or criminality was just as possible for women as for men, and perhaps more so. But whatever their fates, the women discussed in this post need to be recognised as independent actors, capable, within the constraints imposed by their gender, of authoring their own experiences.

It is to one of these tough, resourceful, independent-minded women that we give the last word. In 1732, James, Lord Aberdour hired a new gardener, Mr Rattray, a Scotsman hitherto resident in London, and arranged for him to be shipped back to Scotland. The gardener’s wife, however, refused to accompany him on the journey. As a witness explained:

His wife who is a neat usefull woman aboute a family, being a good housekeeper and understands pestrey work, did not go down with him because she will first see what reception and entertainment her husband meets with and if her husband encourages her, she will soon follow him. She gains a good livelyhood by working in silk for the shops, she is allso a Scotswoman born at Lauder.

Here was a skilled woman of independent means who had clearly carved out her own life in London, and who was not willing simply to give it up without assurances of future prosperity. We do not even know Mrs Rattray’s first name, but she still demonstrates that Scottish women living in early modern London were not to be underestimated.

Further reading

References for all the examples mentioned in this post are available via the Anglo-Scottish Migration wiki: http://wiki.angloscottishmigration.humanities.manchester.ac.uk/index.php/Main_Page

K.M. Brown and A. Kennedy, ‘Land of Opportunity? The Assimilation of Scottish Migrants in England, 1603-ca. 1762’, Journal of British Studies, 57:3 (2018), 709-35

K.M Brown, A. Kennedy and S. Talbott, “Scots and Scabs from North-by-Tweed’: Undesirable Scottish Migrants in Seventeenth- and Early Eighteenth-Century England’, Scottish Historical Review, 98:2 (2019), 241-65

S. Nenadic (ed.)., Scots in London in the Eighteenth Century (Lewisburg, 2010)

Comments are closed.