Jill Dye is a second-year PhD Student on a SGSAH-funded Applied Research Collaboration with the Universities of Stirling and Dundee and the Library of Innerpeffray. Though her PhD research focuses on borrowers from the Library of Innerpeffray 1747-1854, Jill has been using the archives at the University of Stirling to research the borrowers from another of Scotland’s early libraries as part of the Scottish Universities Research Collections Associate Scheme (SURCAS) Pilot.

The Library at Innerpeffray (founded c.1680) and the Leighton Library, Dunblane (founded c.1684) are both open as attractions for any visitor keen to explore historic books in their historic settings, just a 40-minute drive from each other. However, despite their close foundation dates and geographical proximity, the libraries have never yet been studied together. This post considers the links, similarities and differences between these two historic Perthshire libraries.

Foundation

The Library at Innerpeffray was founded c.1680 by David Drummond, 3rd Lord Madertie (1611-1692), when he lodged his own collection of books (c.500 titles) in his private chapel during his own lifetime for the benefit of “young students”. The term “young students” was tested throughout the library’s early history and, thanks to the preservation of borrower records from 1747, we can see that people of all occupations could borrow from the collection without a fee. Hence it has become known as Scotland’s earliest free public lending library. The Leighton was similarly founded by one man, Robert Leighton (also born 1611, dies 1684). Leighton had been Bishop of Dunblane and Archbishop of Glasgow before retiring to Horstead Keynes in Sussex. In his will, he left his large collection of books (c.1500) to “Dunblane in Scotland to remaine there for the vse of the Clergie of that Diocess”. While the intended audience for the collection was different, both collections represent the private books of an individual, contemporaries with each other, both in historic Perthshire, being made public to different degrees.

Collections

The libraries’ collections at their foundation reflect both the nature of their founder and their intended user group. Madertie’s books at Innerpeffray are largely in English and are predominantly religious works, such as sermons, histories or works on practical divinity, largely episcopal in nature. While Leighton operated within the Episcopal church, his much larger library covers a wider range of faiths in an amazing 88 different languages. His is a working library for the interrogation of religious texts, compared with Madertie’s accessible texts to aid the living of a better life. Madertie’s collection, therefore, is of a much greater benefit to the wider public, while Leighton’s befits intense clerical scholarship. Thus, it is clear why the two foundations have never been considered together.

18th Century Management

As early as 1734, however, the nature of the Leighton Library begins to change. The governors decided to introduce a subscription fee so that users other than the clergy of Dunblane could benefit from their collections and to raise funds to update the library collection, which they did. These new acquisitions include not only the latest academic texts but works of interest to a broader public. At Innerpeffray, in 1741, the trustees vow to create a new building for the library and to augment its collections, raising the total number of books to rival the Leighton’s at around 1500. The types of books recommended for inclusion are multi-lingual and reflect a more scholarly-gentleman audience (see here). Thus the libraries’ collections become much closer in nature. The work at Innerpeffray was overseen by Robert Hay Drummond, who eventually inherited the estates of Innerpeffray and Cromlix, near Dunblane. It is perhaps no coincidence that he had a presence on the governing bodies of both institutions, which in itself justifies further exploration in future.

18th Century Use

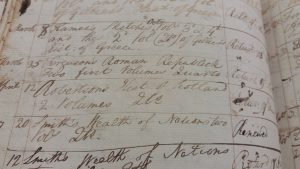

Just as their collections become closer in nature, records of use of both libraries use begin to survive. Innerpeffray’s borrower records are well-known to scholars, unparalleled in their length (1747-1968) and depth (including address and occupation). Less known are the Leighton’s own borrower records, similar in depth, complete for the shorter period 1780-1833. While the Innerpeffray records form the basis of my PhD, thanks to the SGSAH SURCAS project, I’ve now had the opportunity to explore the Leighton’s records too. The type of user is broadly similar (Students, Ministers, Schoolmasters, as well as Surgeons, Architects, Bankers), but Innerpeffray includes a wider range of lower-class occupations (labourers, servants) and those working in the textile industry (weavers, dyers, tailors). This reflects not only the more rural location of Innerpeffray but its lack of fee.

In terms of books borrowed, users are relatively similar in their tastes in genre, but not identical in their choice of titles. Sermons, travel and natural history are very popular genres across both collections. Literature and works of the Scottish Enlightenment are far more present in the Leighton registers, but that reflects their greater presence within the collection. By the nineteenth century, it seems, the Leighton’s subscription model begins to win out, as it supports the purchase of current works, which are popular with the borrowers. At Innerpeffray, however, only a handful of texts enter the collection between 1788 right up to 1854.

In terms of books borrowed, users are relatively similar in their tastes in genre, but not identical in their choice of titles. Sermons, travel and natural history are very popular genres across both collections. Literature and works of the Scottish Enlightenment are far more present in the Leighton registers, but that reflects their greater presence within the collection. By the nineteenth century, it seems, the Leighton’s subscription model begins to win out, as it supports the purchase of current works, which are popular with the borrowers. At Innerpeffray, however, only a handful of texts enter the collection between 1788 right up to 1854.

The opportunity to explore borrowers’ records in one library is astounding, but the chance to compare and contrast them with an equally detailed record is incredible. Despite the differences between the two libraries at their foundation, these libraries, in their borrowers’ records at least, are a valid comparison, provided that their innate differences and the changing natures of both collections across their separate histories is first understood.

The Library of Innerpeffray is open to the public from March-October Wednesday to Sunday.

The Leighton Library is open to visitors from May-September Monday-Saturday 11am-1pm.

For more on the SURCAS project and the Leighton Library borrowers see leightonborrowers.com.

Comments are closed.