Sylvia Valentine is a professional genealogist who is also completing a PhD at the University of Dundee. Her thesis explores opposition to compulsory smallpox vaccination in 19th and early 20th– century Scotland.

Follow Sylvia on Twitter at @historylady2013

The names Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Charles Maitland and Edward Jenner are familiar to anyone researching the history of inoculation. The name Sutton might not be as well-known. The Suttons were a family with origins in East Anglia, and the father, Robert Sutton, devised a method of inoculation known as the ‘Suttonian Method’. Even when the Suttons are mentioned, none make mention of the Suttons having practised in Scotland.

The procedure generally used by inoculators required the patient to eat a restricted diet, since lavish, rich meals were believed to be unhealthy. Patients were also purged and bled prior to being inoculated, and then, being infectious, had to face a period of isolation following the procedure. They were cared for by individuals who had either had natural smallpox of who had been inoculated themselves. And of course, patients could die following inoculation. This did not deter the more affluent members of society from being inoculated, and the inoculation business was a lucrative source of income.

When his eldest son, also called Robert, had a bad experience following his inoculation in 1756, Robert senior set out to improve the technique, thereby developing his ‘Suttonian Method’.

Robert Sutton had been apprenticed to a local surgeon in 1724. He married in 1731 and had a large family, including several sons who eventually worked in the family business. He rented a house where patients were provided with board and lodgings. They paid anything up to seven guineas a week, excluding tea and wine, making the Sutton business extremely lucrative. The Sutton technique was shrouded in mystery, but whatever was involved, his method was deemed to be a great success and the business grew.

As Sutton’s sons grew older, they became involved in the family business. Daniel, who was the most successful of the Sutton brothers, practised in London with the assistance of his brother William. Of the other brothers, Robert junior practised in Norfolk and Paris; Joseph plied his trade in Oxford; and Thomas went to the Isle of Wight. James went to Yorkshire, and it was this Sutton brother who briefly ventured north to Edinburgh in 1771.

Attempting to protect his business from imposters claiming to use the Suttonian technique, Robert Sutton senior placed an advertisement in the London Evening Post in May 1771. He named each of the men who had been trained in the method, and the locations of their businesses, including son James in Scotland. The Suttons were running what today we would recognise as a franchise system. They received a percentage of the fee income generated by their partners.

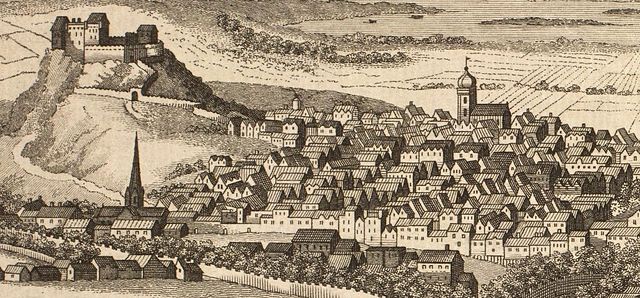

The advert identified two other Suttonian partners in Scotland: Mr Baddeley and Mr Deans. James himself advertised his presence in Scotland in the Caledonian Mercury in March 1771. Deans placed an advertisement on 15 April 1771 suggesting James ‘had not taken care to be properly informed’ that Deans was a Sutton partner. James Sutton’s stay in Scotland was short and by June, he announced he had left Edinburgh for the summer in order ‘to practice inoculation at Gainsborough in Lincolnshire’ and that he proposed to attend to patients at a distance and his fees were between one and six guineas.

Having successfully packed James back to Lincolnshire, Deans continued his inoculation practice until 1776. Planning to leave Edinburgh, Deans advised the public he had instructed the Edinburgh surgeon William Anderson in his inoculation technique. Whilst nothing can be found to identify Baddeley, John Deans, surgeon of St Andrews Street Edinburgh, can be found in Williamson’s Directory for the city of Edinburgh, Canongate, Leith, and Suburbs, 1775-6 and the Caledonian Mercury. Deans was from Falkirk, where he had been inoculating children around and about Stirlingshire. He planned to come to Edinburgh and sent potential patrons to notify their interest with the brewer Mr Anderson at the back of Canongate. Neither the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh nor the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons in Glasgow have evidence that either Deans or Baddeley were members.

It is difficult to assess the extent of the Sutton’s influence on inoculation practices in Scotland, but at least one respected member of the Scottish medical community knew of their techniques. Amongst the papers of Sir James Pringle, held at the Royal College of Physicians, is a document from 1768 which confirms Pringle was an admirer of the Suttons.

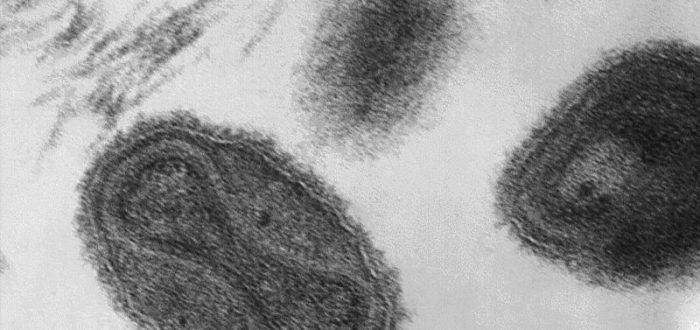

By the last decade of the eighteenth century, Edward Jenner’s experiments in the use of cowpox lymph led eventually to its dominance of the smallpox inoculation market. The age of vaccination dawned at the start of the nineteenth century and by the mid-1800s the use of inoculation as a preventative for smallpox was outlawed.

Further Reading

M. Bennett Michael, War Against Smallpox, Edward Jenner and the Global Spread of Vaccination (Cambridge, 2020)

C.W. Dixon C.W. Smallpox (London, 1962)

I. Glynn and J. Glynn, The Life and Death of Smallpox (London 2005)

P. Razell Peter, The Conquest of Smallpox (Firle, 1977)

J.R. Smith, The Speckled Monster: Smallpox in England 1670 – 1970 with particular reference to Essex (Essex, 1987)

G. Weightman, The Great Inoculator, The Untold Story of Daniel Sutton and his Medical Revolution (New Haven and London, 2020)

G. Williams, Angel of Death, The Story of Smallpox (Basingstoke, 2010)