Lisa Baer-Tsarfati is a PhD candidate at the University of Guelph, whose research uses natural language processing and word embeddings (vector space modelling) to examine how language was used to exert control in early modern Scotland. In this special guest post, she discusses what family tradition around one 16th-century Perthshire marriage can tell us about matrimony, divorce and concubinage in early modern Scotland.

Follow Lisa on Twitter at @baersafari

Late in the summer of 1581, Margaret Tosheoch was contracted to marry Archibald Campbell, fourth son of Sir Colin Campbell of Glenorchy. Their union had been negotiated by their fathers and their contract of marriage witnessed by half a dozen Perthshire gentlemen. As contracts go, theirs was unremarkable, outlining the terms of conjunct fee and jointure, tocher, and the tochers of any daughters born to the married couple. For her tocher, Margaret brought a small sum of money and the promise of her future inheritance, for, as the sole child and heir of Andrew Tosheoch of Monzie, Margaret stood to inherit the quarter lands of Monzie, an estate situated some twenty miles southeast of the primary Glenorchy residence of Taymouth Castle. That the Campbells should thus have pursued an heiress for the marriage of a younger son is unsurprising, for the family had long shown a proclivity to acquire land by marriage.

No evidence survives to prove that the contracted marriage between Margaret and Archibald was ever formally honoured; however, family tradition holds that the marriage was solemnized but the union unhappy. Though Margaret and Archibald were childless, Archibald fathered several children on one of the daughters of Gregor Roy MacGregor of Glenstrae, living in open concubinage with his mistress before bigamously marrying her in 1600 or 1601. In response, Margaret sought a divorce but was refused by her husband. Outraged, she seized her contract of marriage, tore her signature from the page, and ate it in front of her astonished spouse. Margaret was then sued by her father-in-law for ‘spoiling’ her marriage contract in March of 1601.

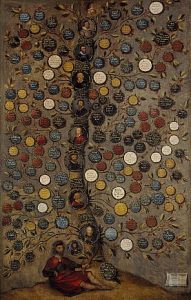

The family tree of the Campbells of Glenorchy (1635), by George Jamesone

Margaret and Archibald’s contract of marriage is still preserved within the family papers of the Campbells of Glenorchy held by the National Records of Scotland. The surviving contract bears the signatures of both sets of parents, the bridegroom, and the witnesses, yet conspicuously absent is the signature of the bride, which appears to have been torn away. As damage to manuscripts is moderately common, little can be interpreted from the existence of the tear itself. That said, the absence of Margaret’s signature in such material circumstances would seem to corroborate the details of the family narrative; unfortunately, nothing else about the historical record does.

As previously noted, it is not clear whether the contract of marriage negotiated between Margaret and Archibald ever resulted in an actual marriage. If it did, there is no evidence to indicate that it was unhappy or that Margaret was ever sued by her father-in-law. No account of any court proceeding in which Margaret Tosheoch was ever called to compear can be found in any Scottish court records. More damning still is the fact that Sir Colin Campbell, sixth of Glenorchy, died in 1583. There is no possible way that Margaret could have been sued by Sir Colin for any transgression in 1601. Yet, this family tradition has been passed down across the centuries, painting a vivid picture of a high-spirited, but ultimately tragic, figure. Margaret Tosheoch is portrayed as a woman trapped in a loveless marriage, tied to an adulterous and bigamous spouse, and persecuted by a greedy and contentious father-in-law. However, she was also a woman willing to resist this treatment by pursuing a divorce, or by attempting to invalidate her contract of marriage when divorce was denied her. Margaret’s story has been mythologized over time, offering a fascinating glimpse into not only the marital practices of elite society in early modern Perthshire but also the attitudes surrounding marriage, divorce, and concubinage in the central Highlands of the sixteenth century. A further investigation of marriage, divorce, and concubinage in early modern Perthshire follows, to properly situate the myth of Margaret and her marital woes into the cultural practices of the society in which she lived.

Marriage in early modern Perthshire

Although marriage in early modern Scotland was an institution that prioritised concerns about lineage and association, it was also a practice that was largely shaped by transparent economic considerations. Surviving contracts of marriage attest to this, highlighting the financial importance of marital alliances by the formulaic way in which they were structured. Such contracts laid out the terms of the couple’s conjunct fee (the lands to which they both held title), the bride’s future jointure (an annual payment made to a widow from her husband’s estate to ensure her future maintenance), and the bride’s tocher, or dowry, as well as its method of intended delivery. While it had been standard practice for tochers to consist of cattle (and sometimes ships) in medieval Gaeldom, by the sixteenth-century, dowries throughout Scotland were increasingly paid out in cash. Among the marriages contracted by members of the Perthshire elite between the years 1500 and 1650, all appear to have followed this trend, and in all other respects, marriages in early modern Perthshire tended to follow the prevailing patterns of marriage demonstrated elsewhere in Lowland Scotland.

These patterns included a period of betrothal, which could be of any length of time, and then the solemnization of the marriage. While marriage contracts usually materialized into actual marital unions, the occasional failure to complete a contract of marriage was not entirely unknown. Sometimes these arose from personal motivations and sometimes from political motivations and could represent either a broken betrothal or the abandonment of negotiations between families. In the case of Margaret Tosheoch and Archibald Campbell, their contract of marriage could have resulted in an actual marriage or it could have been the surviving record of an abandoned betrothal. Either outcome is equally possible according to the historical record.

In negotiating marriages for themselves and their children, Perthshire elites conformed to the general trends observed by their peers across Scotland in the matter of partner choice. Overwhelmingly, Perthshire contracts of marriage were transacted by parents on the behalf of their children, and the importance of rank and pecuniary factors is supported by the sheer number of contracts that survive. Perthshire elites tended to marry others of equal or greater rank to themselves, with marriages between different lairds and their children accounting for nearly 70 percent of all marriages solemnized by the Campbells of Glenorchy, the Stewart and Murray earls of Atholl, and the Robertsons of Clan Donnachaidh. Between 18 and 20 percent of marriages involved marriage to a peer or his child, while around 5 percent of men married the daughters of Highland chiefs and around 10 percent of women married chiefs of their sons. Examining the terms of property exchange in these contracts reveals that nobles within Perthshire, like their counterparts elsewhere in Scotland, were not strangers to the practice of trading money for rank. Equally, and particularly among the younger sons of the Campbell lairds of Glenorchy, financial considerations often led to brides being drawn from the ranks of local heiresses, daughters who were the sole children of their fathers and whose tocher in land holdings might substantially widen the sphere of influence exercised by this shrewd and ambitious family. According to the family tradition, Margaret clearly fell into this final category.

Divorce and concubinage in early modern Perthshire

Following the Reformation, divorce in Scotland could be obtained on the grounds of adultery or abandonment, and divorced individuals were no longer barred from remarriage. Although adultery had been an accepted basis for a form of marital annulment since the Middle Ages, there remained throughout the Gaelic world a more lenient attitude toward concubinage and even polygamy. Yet, if the keeping of mistresses (albeit as publicly acknowledged concubines) was to some degree more acceptable in Gaelic society, it was by no means a practice limited to the Highlands given the number of illegitimate children born to peers and nobles throughout Scotland. Still, there remained a greater stigma against extramarital sex within Lowland society than, perhaps, outside of it. This, it would seem, is reflected in the tradition of Archibald Campbell taking a second wife while still married to Margaret.

Sir Colin Campbell of Glenorchy, from the Black Book of Taymouth

Prior to 1560, a small handful of dissolved marriages were recorded in Perthshire, but all were the result of consanguinity, either upon the failure of the couple to obtain a proper dispensation when connection was known, or upon the discovery of the connection when it had previously been unknown. While individuals whose marriages had been dissolved for adultery were unable to remarry according to the laws of the Catholic Church, those whose marriages had been dissolved due to blood-affinity could. After the Reformation, this changed and those who had been divorced for adultery could remarry. Of the forty-five marriages solemnized between 1574 and 1610, five ended in divorce following an accusation of adultery. That Margaret Tosheoch should thus desire a divorce due to her husband’s adultery demonstrates, if not the actual rise in this trend, then at least shifting attitudes towards divorce and the unwillingness of women to tolerate their husbands’ infidelity.

Wives who were found guilty of infidelity and subsequently divorced in early modern Scotland could expect to forfeit their tochers while husbands found guilty of infidelity and subsequently divorced could expect to lose whatever property their wives had been infeft in (granted for their maintenance) according to the terms of their marriage contract. In a Gaelic context, it had been common practice upon the dissolution of a marriage for the separating parties to return to their families in possession of whatever property they had brought into the marriage, yet there is little evidence to suggest that this custom, rather than Scottish jurisprudence, influenced the material outcome of sixteenth-century Perthshire divorces. Yet, the implied fear in Margaret’s story, is that a successful divorce would result in the Campbell’s forfeiture of control over the quarter lands of Monzie. Whether this reflects a Gaelicized attitude toward property, it nevertheless explains Sir Colin’s legal action against Margaret’s ‘spoiling’ of her marriage contract. For, according to the legal tradition, a contract of marriage was only valid if it bore the signatures of both prospective bride and groom, as the Kirk required the consent of both parties in order for the marriage to take place. By removing her signature from her contract of marriage, Margaret was effectively revoking her consent to the union, and perhaps, in the lay understanding of the law held by members of a family perpetuating the myth, invalidating her marriage in the process.

In spite of the expense and complications associated with early modern divorce, 11 percent of the marriages involving Perthshire nobles between the years of 1570 and 1605 were dissolved by the commissary court in Edinburgh. That all of these cases should have involved adultery of at least one partner, even if adultery was not always stated as the primary motivation for the divorce, is interesting given the laxity of Celtic attitudes toward concubinage, polygamy, and divorce. Though not all marriages troubled by infidelity were dissolved (Duncan Campbell, seventh of Glenorchy, had at least a dozen illegitimate children, many of them born during his wives’ lifetimes), several were. The trend reveals a somewhat persistent permissiveness toward extramarital relationships, often on the part of male elites, and a growing intolerance on the part of female elites for their husbands’ extramarital affairs. While a myriad of other factors may have influenced this discrepancy in perspective, it might still be indicative of the drawing away from Gaelic patterns of marriage behaviour in favour of post-Reformation Lowland ideas, particularly at the instigation of elite women in the central Highlands.

Celtic secular marriage made allowances for concubinage, polygamy, and divorce, and did so with a fairly permissive attitude not shared by canon law or Lowland legislation. Although divorce became easier to obtain after the Reformation, in wider society, it was still fairly rare, accounting for only 3 percent of marriages involving the higher nobility. Yet, within Perthshire, 11 percent of the marriages solemnized between the years of 1570 and 1604 ended in divorce. The trend here appears to have supported a general attitude of laxity toward concubinage with three of the primary nobles in Perthshire fathering multiple illegitimate children in line with the earlier Celtic model, particularly when a wife’s fertility was brought into question. In spite of this, the women, themselves, appear to have been the driving factor in any shift in attitude on this matter as all five of the recorded divorce cases having occurred in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Perthshire were initiated by unhappy wives. In most of these cases, the divorce was granted on the grounds of a husband’s infidelity and property was divided accordingly, with the men forfeiting their wives’ tochers as well as whatever properties had been promised for her maintenance in the marriage contract. That is, if not the actual ownership of the property, then at least the income derived from it, as a woman might bring action against her ex-husband for not providing for her maintenance. In most cases, it appears that the greatest impetus of change in sixteenth-century Perthshire came at the hands of women. Thus, the tale of Margaret Tosheoch’s marital woes, although most likely historical fiction, still reveals a shift in attitudes toward marriage, divorce, and concubinage borne out by the historical record. In this way, it is both a delightful story and an excellent gateway to understanding the practice of marriage in the early modern central Highlands.

Further reading

NRS, Breadalbane Muniments, GD112/25/40, Antenuptial contract of marriage between Archibald Campbell, Illanran and Monzie, fourth son of Colin Campbell of Glenurquhay, and Margaret Toscheocht, eldest daughter of Andrew Toscheocht of Monzie and Elizabeth Toscheocht, his spouse [22–24 August 1581]

K.M. Brown, Noble Society in Scotland: Wealth, Family, and Culture from the Reformation to the Revolution (Edinburgh, 2000)

G. MacGregor, The Red Book of Perthshire (Perth, 2014)

R.K. Marshall, Women in Scotland, 1660–1780 (Edinburgh, 1979)

R.K. Marshall, Virgins and Viragos: A History of Women in Scotland from 1080 to 1980 (London, 1983)

W.D.H. Sellar, ‘Marriage, Divorce, and Concubinage in Gaelic Scotland’, Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness 51 (1978), 464–93

Comments are closed.