I am a Senior Lecturer in European History at the University of Dundee, and I co-teach HU42001 (History of the Book, 1500-1800) together with Dr. Jodi-Anne George, my colleague in the English Department.

I am a Senior Lecturer in European History at the University of Dundee, and I co-teach HU42001 (History of the Book, 1500-1800) together with Dr. Jodi-Anne George, my colleague in the English Department.

I became interested in the archeology of archives and materiality of texts as a Fellow of the Netherlands Institute of Advanced Study in 2005. I have a book contract with Brill Academic Publishers to publish a monograph on the working papers of the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius (1583-1645). These voluminous materials –thousands of folios are extant today— moved in and out of public view over a period of three centuries. This resulted in the creation of what I call ‘different faces of Grotius’: Grotius as Remonstrant martyr, as a Dutch patriot and republican, as father of international law, etcetera. Since we cannot have immediate access to the past, we make inferences on the basis of archival materials that are really palimpsests, i.e. layers-upon-layers of evidence, selected and created by the generations that have gone before us. How this process has shaped our understanding of Grotius’ nachleben, I intend to explain in my monograph.

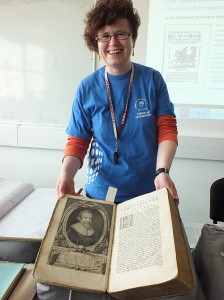

Philippe de Mornay, De la vérité de la religion Chrestienne, contre les athées, épicuriens, paiens, Juifs, Mahumedistes & autres infidèles..(1582)

Brechin Collection230.2 M 866

USTC REFERENCE NO: 89746

The USTC project in St. Andrews identifies this edition, published by Jean Richer in Paris in 1582, as being extremely rare. There are only two extant copies in the world, i.e. one in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris (Paris (Fr), Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal 8o T 8475) and the other in the Brechin Collection here in Dundee. The USTC project allows libraries around the world, including Dundee University Library and Archives, to determine which objects in their collections are truly rare and valuable, and therefore deserving of extra care, certainly when it comes to preservation and restoration. The copy in the Brechin Collection reveals that strips of vellum containing printed text have been used for for the binding of this book. Perhaps these vellum strips are remnants of a lost incunabel? (Printing on vellum was far more common in the second half of the fifteenth century than in the sixteenth century.) It would be interesting to see whether the vellum strips can also be found in the copy in the Bibliothèque Nationale. The ‘Lost Books’ conference in St. Andrews in June 2014 is the latest contribution in a lively historiographical debate on the vexed question of how we arrive at reliable estimates of the quantities of manuscripts and printed books produced and lost in the pre-modern world.

Comments are closed.